Although charming pets for some people, squirrels are not for everyone. No matter how early they are acquired, they remain essentially wild animals whose instincts, throughout their lives, keep them in a perpetual state of alert to potential danger. They are far from the ideal pet for children. A squirrel will never tolerate hugging, rarely petting. Simple holding is a threat, because it restricts the animal’s ability to flee in an instant. If squeezed inadvertently even the smallest, shyest, most gentle squirrels will automatically retaliate with a bite that can pierce a finger, nail and all.

The squirrel will do little to accommodate to you. You either keep it in an adequate cage — or you decide to accommodate to it, in order to really get to know the animal. The owner who allows these animals outside their cages in the home must be prepared to pay a price in chewed, scratched furniture — and drapes, which are by the squirrel’s definition its territory. Housebreaking, except in the most literal sense of breaking a house, is impossible.

While a squirrel might obviously enjoy playing on people as if they were frees, it takes no delight in playing with them. This kind of sport will not endear the owner to guests wearing nylon hose, and bare legs simply mean the squirrel must, and will, find something else to dig its claws into as it charges upward.

And yet, with the varied habits and personalities of the different species, you might well find an animal ideally suited to your particular life-style. Take the working couple, for example. Wouldn’t a nocturnal animal such as a lovely, gentle flying squirrel make an ideal pet? It sleeps all day while they are at their respective jobs. When they return home, it is ready and eager to get out and soar gracefully from room to room. And it is affectionate, delighting in climbing into pockets where it can curl up into a soft fur ball.

If acquired while very young, some squirrels adapt well to captivity. They are by nature hardy and the care they require presents no great difficulties. Disease is rare, and they are both cautious and nimble enough to avoid accidents.

Different Species

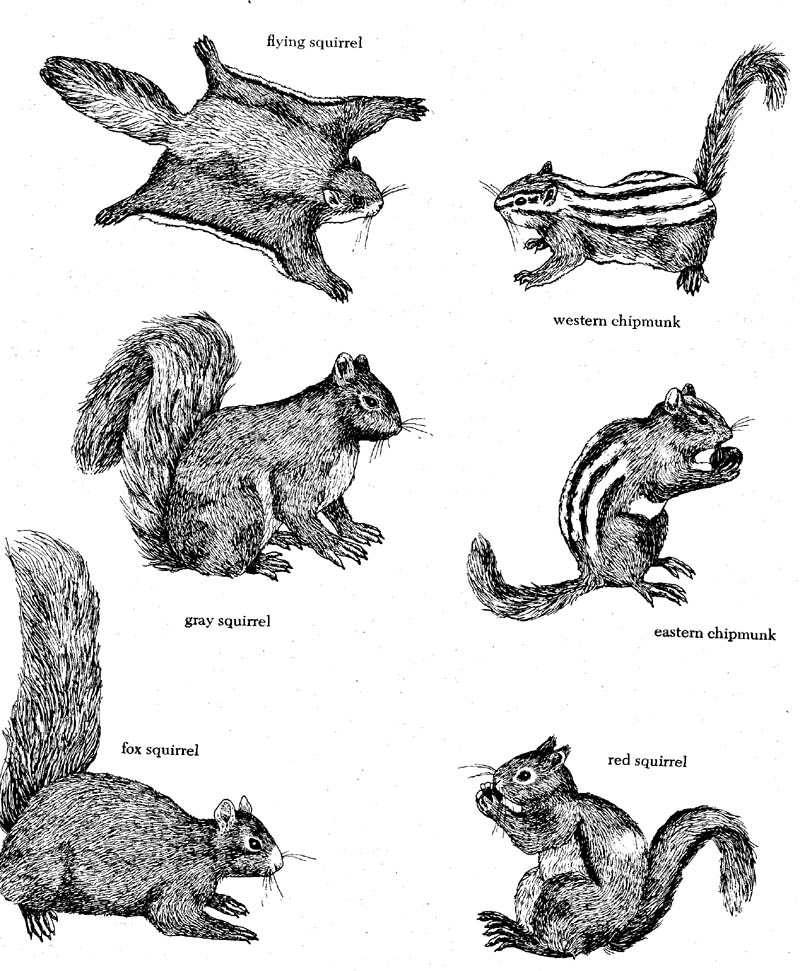

There are far too many species of squirrel in the United States alone to attempt to cover here. Briefly, we will look at the most widespread and numerous of these, those most likely and best suited to become pets. This will show something of the diversity of personalities and illustrate what should be done to keep the different types of squirrel in good health. Different as their behavior might be, the care needed by one species of tree squirrel is the same as that needed by another. The chipmunk is distinguished in many ways from the true ground squirrels, yet the kind of treatment that is best for it will be equally good for other ground dwellers. The two species of flying squirrels have identical needs that must be satisfied if they are to remain healthy and happy.

GRAY SQUIRRELS

As they make the rounds of park benches, sifting up without the slightest sign of shame to ask for a handout, these most familiar of our native tree squirrels prove just how misleading it can be to try to categorize animals. A large part of their lives is spent on the ground, both looking for food and finding places to bury the surplus of the moment for the lean times ahead. The tree is there for nesting, rearing the young, and as a retreat in danger. The earth is for activities certainly no less important.

No squirrel has adapted better to man’s invasion of its environment than the eastern gray, the dominant species within the genus Sciurus, animals with greater or lesser physical differences but basically similar in their personalities and habits. The prime reason for their success in living side-by- side with man is personality. Among tree squirrels, the grays are comparatively easygoing types, not so quickly given to panic but quite ready to put up a defense if pushed too far. Some, in fact, actually become aggressive, suddenly launching unprovoked attacks on humans. Though they grow to no more than 18 inches in length, half of which is bushy tail, an attack by an animal with razor-sharp teeth in a jaw powerful enough to open the shells of black walnuts is nothing to be shrugged off lightly.

The likelihood of such physical attacks is minimized if you get a gray young enough. They often prove to be very much one-person pets and very infrequently attack their owners. Interestingly, some assaults reported to take place in parks are believed by certain naturalists to be characteristic of pets that have been abandoned, rather than animals that grew up wild.

It was the impressive tail, incidentally, that gave this genus its name. Sciurus, Latin for “squirrel,” had its own roots in Greek: skia (shadow) and oura (tail), or shade-tail, because the animal holds his brush up as though it were an umbrella.

In appearance, the gray is a handsome animal with his dark salt-and-pep per to tweed brown to black back and light gray undersurface. The interesting shadings result from the fact that each guard hair is made up of bands of different colors. The western gray, whose range picks up in the Dakotas and extends to the Pacific Coast, is distinguishable from its eastern relatives only by its larger size, ranging up to 22 inches in length.

FOX SQUIRRELS

A shyer member of the genus, the fox squirrel, has retreated from large parts of the heavily inhabited Northeast. Oddly, however, fox squirrels have been successfully introduced to parks in cities. Largest of the tree squirrels, the fox reaches a full 2 feet. This heavily built animal comes in a number of striking color variations — gray, buff, or black with white ears and tail. Like the eastern gray, its range ends in the Dakotas to the west. While the gray prefers low timberlands, the fox squirrel is found in country with alternating groves and open land.

But color variation is common in this genus. Melanistic (black) gray squirrels occur frequently, and albinos have even become dominant in some isolated communities, Among the most dramatic of the species are the Albert’s and kaibab squirrels found in the Rocky Mountains, with bobcat tufts of long hair tipping their ears, reddish backs, and white or off-white tails.

RED SQUIRRELS

These, the smallest of the native tree squirrels, belong to the genus Tamiasciurus. Very obviously, the red considers size of little importance. Pugnacious creatures, they haven’t the slightest hesitation in attacking larger grays indiscreet enough to invade their territory, and invariably put the intruder to flight. These chases rarely if ever lead to actual combat, however. If the gray is trapped on the end of a branch, the red will keep its distance, content to scold. While human interlopers need not fear actual physical assault, they too receive ample attention when they enter the range of these watchdogs of the forest. The stream of insults that follows has earned the red such names as chatterbox, barking squirrel, and boomer.

Eastern reds range up to 14 inches in length, 5 inches of which is tail, and weigh no more than ii ounces. The somewhat smaller Douglas red squirrel, or chickaree, of the West, is distinguished primarily by color. The general appearance is a rusty red with a gray vest.

These animals are far more excitable than the gray squirrels and are there fore not so easily adaptable to the role of pet. In captivity, tree squirrels have lived up to twelve years.

CHIPMUNKS

Chipmunks, the most widespread of our native ground squirrels, have at times made gentle, hardy pets. There are two groups of these handsome little animals: the eastern chipmunk (Tamiasstriatus), which ranges from the Atlantic Coast to the Dakotas; and the western, or least, chipmunk (genus Eutamias) with a range extending from the Great Lakes to southern Alaska. There are around sixteen species of the latter, distributed through most of the western states.

The basic colors of the eastern chipmunk are a rusty or brownish red or the back and light gray to white undersurface. The back is marked with five dark brown to black stripes, extending to the base of the tail. These alternate with two gray and two white stripes. The eye is offset with a dark stripe, outlined above and below by buff stripes. While it has a proportionately long tail, the chipmunk’s lacks the bushiness of tree squirrels’. Eastern chipmunks grow to between 8 and 12 inches.

The western chipmunk tends to be smaller, rarely reaching 9 inches, and is more slender. Its color is more grayish than that of the eastern species. The stripes, while they maintain the same pattern of alternating dark and light, are thinner and more closely placed.

Chipmunks are more easily tamed than tree squirrels. Members of the western species are less shy and adapt more readily to life in captivity. As pets, chipmunks have lived as long as seven years.

FLYING SQUIRRELS

Flying squirrels, of the genus Glaucomys, are the most interesting and, with their large, soft eyes, possibly the most attractive of our native squirrels. Furthermore, despite the drawback of their being nocturnal, some of these gentle, sociable animals make excellent pets.

These animals do not actually fly despite their name, but glide from branch to branch or to the ground, covering distances as great as 125 feet. This is made possible not by wings, as in the case of the bat, but by expansible, furred membranes that run from the wrists of the forelegs to the hind feet and then to the base of the tail. When the squirrel leaps into space, it extends its legs, drawing the membranes taut and giving them the surface area necessary to soar. The flattened, featherlike tail is used for guidance. As the squirrel nears a tree trunk it wants to land on, it swoops upward at the last instant, making contact with all four feet. In the forest, you can hear the thumps as they land.

There are two native species, the northern flying squirrel — which ranges in the East from Labrador as far south as Georgia, and in the West from Alaska down to southern California — and the southern — which overlaps its cousin’s range southward and eastward from Minnesota.

The larger northern flying squirrel grows up to 14½ inches in length, and weighs up to 6½ ounces. The southern does not exceed 10¼ inches and weighs no more than 4 ounces. The tail is almost half the animal’s length. The undersurface of both species is a gray to cream white. While the upper surface of the northern flying squirrel is a soft, dark gray, that of the southern may range to a reddish brown. Pet flying squirrels have been known to live up to eight years.

Although the northern chipmunks retreat to their burrows for the winter, none of the squirrel family truly hibernates. In captivity, with a continuing supply of food, these animals should remain active throughout the year.

Preventive Medicine

FINDING A PET

None of these animals breed readily in captivity, so there is no true commercial supply. The prospective owner, therefore, must either rely on luck — such as finding a foundling or knowing someone whose animals have successfully mated — or secure a rarely available tame adult. The latter are to be approached with caution. Obviously, they are former pets and there is automatically the question of why they were given up. In the case of a red, inclined to be very much a one-person pet, it would be almost impossible to fit it into a new home.

Ideally, you should look for a squirrel no older than six weeks. Red squirrels are born in May and June, eastern grays around the end of January and in mid-June, western grays in the late winter or early spring, flying squirrels in late March and early April, and chipmunks usually in April.

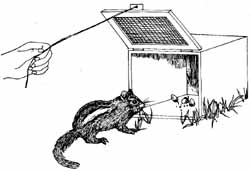

For securing chipmunks, traps are one method and the most suitable are the box variety. These are simply made with a drop door, which is triggered remotely by a string once the animal has been lured in. Precise age is not so crucial a factor, though youth is desirable and it would be best to trap your pet during its first days of exploration outside the nest. Grass seeds, berries, or acorns can serve as bait. Patience is a necessity.

The bait should be placed at the far end of the cage so that there is no possibility of the animal’s being hit by the door as it descends. Regardless of species, any new animal that shows a tendency to bite should be promptly returned to the place from which it was taken.

HOUSING

Until the baby becomes active and shows that it is ready to begin inspecting its new home, housing is primarily a matter of protecting it from chills. Any small, strong, dry box will serve adequately if it is lined with clean, soft cloth such as flannel, or dry grass. Change regularly for cleanliness.

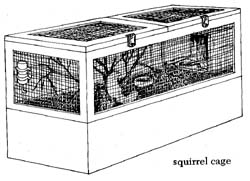

When it does start getting around, you can purchase a cage suitable for an adult squirrel at a pet store. If you plan to build your own, remember that these are gnawing animals; unless you plan on giving the squirrel the freedom of the house, you must be prepared for escape attempts. These can be forestalled by covering the wooden supports with wire or metal. Use 14- gauge welded wire for the sides and top. The bottom may be cut from heavy plywood and given sides that rise to 18 inches.

Squirrels need sufficient space in which to move around and to exercise. For a tree squirrel, a cage 6 feet long by 4 feet high by 3 feet wide would not be excessive. In it, place a tree limb large enough to extend from floor to ceiling and anchor it firmly at top and bottom. Chipmunks can have proportionately smaller cages and do not need a limb to climb on. An exercise wheel, however, is extremely important.

The floor of the cage can be covered with wood shavings, leaf mold, or soil to a depth of at least 1 foot. The covering should be changed at least twice a year. If leaf mold or earth are used, they should be dampened but not soaked whenever they become dry. This serves to prevent parasites. The cage should be kept where it will get sunlight in the morning.

Facilities and materials for a nest must be provided. For tree and flying squirrels, the nest can be a wooden box with adequate space for the animal or animals to sleep comfortably. This must be raised off the cage floor, either on a shelf or bracketed to the side of the cage. One end should be open. A hollow log makes an ideal nest for a chipmunk.

The animal will construct its nest from the materials you put in the cage. These can vary, including coarse shavings, shredded paper, kapok, grass, and soft hay. Because it catches on the squirrel’s claws, no form of floss should be used.

If your squirrel or squirrels are regularly allowed the run of the house, cages need not be so large. A large, ceiling-high limb with sturdy branches should be firmly mounted in one corner to give tree squirrels a place to climb and scamper. Cages for tree squirrels and chipmunks should be left open during the day and provided with entrances that make it easy for the animal to scamper in and out at will for food and water when it is let out.

While tree squirrels and chipmunks can be kept permanently caged, there would be no point in keeping flying squirrels if this were your intention. The animal could live nothing remotely resembling a normal life.

Tree squirrels are territorial and it is rare that one will accept others either in its cage or in the same house unless they are lifter mates. Chipmunks, while they live individually, are much more tolerant of others of their kind, and several can usually be kept together. Flying squirrels, on the other hand, are sociable creatures who normally share their nests in the wild and are actually happier in a group.

GROOMING

A pet that cannot be held is hardly likely to be cooperative in any attempts at grooming. Fortunately, squirrels are conscientious about grooming them selves, and no efforts are needed.

Despite the discomfort they might cause when the squirrel decides that you are a walking tree, its claws should never be trimmed. These are essential to the animal’s activities and you would be endangering it by doing so.

In one respect you can aid your squirrel in its own personal grooming: there should be items in the cage that make it possible to sharpen its teeth. Rock salt, which can be purchased at pet or food stores, is ideal, because it is also desirable from a dietary standpoint. Hard-shelled nuts are good for larger squirrels but of little use to chipmunks or flying squirrels, which do not regularly feed on them.

FEEDING

Food should always be at hand, particularly for the rapidly growing younger animals. Squirrels and chipmunks regulate their own diets, according to need. The ideal staple diet, both nutritionally and from the standpoint of convenience and expense, is hamster pellets. These should be supplemented with fruits, including berries, apple or orange slices, and melon seeds and rinds.

Fresh greens, such as spinach or lettuce, are also necessary to the animal’s diet. Any kind of seeds and grain will be welcome. Tree squirrels are especially fond of mushrooms and will take them either fresh or dried.

Occasionally, larger squirrels should be given a few nuts. For economy’s sake, gather acorns from beneath the nearest oak rather than pay the inflated prices of luxury nuts. Hard-shelled nuts are actually of more value for tooth- sharpening than nutrition.

WATER. There should always be a supply of fresh, clean water in the cage. The best means of providing it is with a hamster bottle, which can be obtained at any pet store.

TRAINING

In the strict sense of the word, squirrels cannot be trained. They can, how ever, learn things when there is a proper reward. For example, they will delight in investigating your pockets if you customarily carry a treat in them. The smaller chipmunks and flying squirrels will learn to eat sifting on your hand. Bear in mind, while attempting to train your squirrel in this fashion, that it will have no tolerance whatsoever for being teased. Holding a nut too firmly for the pet to take, or grasped in a fist, will earn a painful bite.

FLYING SQUIRRELS AND OPEN WATER

In general, squirrels are extremely cautious creatures, alert to all possibilities of danger. Thus, there is little possibility of their causing injury to them selves. There is one strange exception, however. Though they are unable to swim, flying squirrels are extremely fond of water. Any open water in a home in which there are flying squirrels is an invitation to drowning.

Illness and Injury

Obviously, with an animal that cannot readily be held, there is little that the layman can do in the event of illness or injury. Even such routine examinations as taking temperature or checking for fleas require professional care. Serious traumas are almost inevitably the cause of death, for the animal’s nervous system is incapable of handling the strain. Death from shock is swift and, fortunately, painless.

The best that can be done is to remain alert to symptoms of illness. These are:

- Bald patches or severe loss of hair (this does not include spring

- shedding of the winter coat)

- Sniffling or running nose

- Running eyes

- Diarrhea

- Scratching

All of these should be signals to take the animal to a veterinarian. There is simply no sense in getting badly bitten attempting to diagnose and treat problems yourself. While we are on the subject of both biting and illness, it might be well to point out that though squirrels are subject to rabies, no case has ever been reported of a human contracting rabies from a squirrel bite.

Squirrels are incredibly hardy animals with a strong resistance to infections and, living in a home, the opportunities of their picking up any transmissible disease are extremely limited.

Mating and Babies

Mating squirrels is largely a matter of determining whether they are willing to share quarters and are of opposite sexes — then leaving it in their hands (or paws) from that point. Sexing is best done while the animal is still young enough to permit handling. Pressure from a gentle finger immediately in front of the anus will reveal either the bulbous head of the penis or the distinctive fore-and-aft slit of the vagina. Females are usually ready to breed by the end of their first year, though some flying squirrels do not do so until their second.

With sociable animals such as the chipmunks and flying squirrels, there is little difficulty in introducing the male to the female. With the tree squirrels, the situation is somewhat more tricky. The best way to get over this hurdle is to bring them together on neutral ground, in a cage unfamiliar to either. Any immediate hostility will be overcome by the desire to explore the new environment, and territorial defensiveness will not provoke attacks.

MATING

Mating seasons vary in number regionally and it is difficult to predict just what the pattern might be with squirrels reared inside households. Mating might take place in the spring, in the summer, or even in the winter. Litters usually consist of from two to five young, though there may be only one or as many as seven. At the indication of any hostility by the mother, the father should be removed from the cage.

BIRTH

Squirrels are excellent parents; if breeding is successful, the mother should simply be left alone. No human intervention is required at any time. When the young are born, they should not be interfered with until they emerge from the nest on their own initiative. The gestation period is approximately one and a half months, with some slight variation by species — though this is no greater a factor than individual differences.

HOUSING

No special nesting box is necessary if the babies are sharing the mother’s nest, though if you suspect she is pregnant new nesting material should be placed in the cage. Nesting boxes for foundlings or babies removed from the nest are described earlier.

FEEDING

There is no problem feeding the babies when the mother is tending them. She will care for them adequately without assistance until they are weaned.

Foundlings and captured babies are another matter, of course. Age is the prime determinant in what they need. Very young squirrels must be fed every few hours — this time can gradually be lengthened.

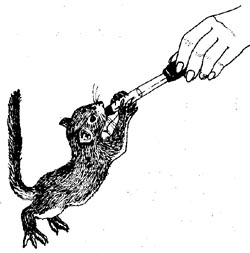

Either a plastic eyedropper or a glass one, with the tip enclosed in a small piece of rubber tubing to protect it from young teeth, is excellently suited for giving the baby its milk. This can be either whole cow’s milk or a mixture half of evaporated milk and half of water. It should be given at body temperature.

While vitamin drops or precooked baby foods, such as Pablum, may be added, baby squirrels should not be given a formula containing any sweetener, which can cause diarrhea. Immediately after feeding, any milk should be removed from the squirrel’s fur with a warm, wet washrag to minimize the chances of diarrhea.

When the baby is able to feed itself, introduce bread soaked in milk, to supplement the bottle and to introduce it to more solid foods. This can be followed by soft fruits and vegetables until the squirrel gets its gnawing teeth, at which time a gradual transition may be made to the adult. By ten or eleven weeks, the squirrel should be completely weaned.

«

»