Chickens can suffer many different health problems from many different sources. If you consult a website or book on poultry, you will find so many diseases listed you may be dissuaded from ever keeping chickens. Most disorders, though, are readily pre vented through good management. Many infectious diseases can be prevented through vaccination and worming. How aggressive you need to be depends on many factors. The intensive husbandry of commercial poultry operations necessitates aggressive vaccination and worming. A well-maintained backyard flock, derived from healthy stock, will not require a lot of preventive medicine. Be aware, though, that backyard flocks that are not vaccinated or wormed can develop problems. If you show your chickens or regularly introduce new birds, you will need to vaccinate and worm more often than if yours is a closed flock, with no travel and no new additions. Consult your veterinarian or Extension agent for advice.

The longer you keep a chicken, the more likely it is to get a disease, which is why commercial growers and many experienced backyard flock owners won’t keep chickens for more than a year or two — as soon as this year’s replacement flock matures, last year’s flock is out the door. Given a little extra care, though, your chickens can remain safe and healthy for many years.

How Diseases Spread

Disease-causing organisms are always present in the environment, but they may not cause problems unless a flock is stressed or kept in unclean conditions. Diseases are carried through the air, soil, and water. They may be spread through contact with other chickens or other animals, especially rodents and wild birds. They may be carried on the clothing, particularly the shoes, of the person who tends the flock.

Wild birds spread diseases by flying from one chicken flock to another, looking for spilled grain. If you live in an area where chickens are common, netting over your chicken yard will keep out freeloading birds.

Visiting other chicken yards is a good way to bring back diseases by way of manure clinging to your shoes. After such a visit, clean your shoes thoroughly before tending your own flock.

One chicken can get a disease from another, even if both birds appear to be healthy. After your flock is established, avoid introducing new chickens. Every time you bring home a new bird, you run the risk of bringing some disease with it. If you do acquire a new chicken, or bring one of your chickens back from a show, house it apart from the rest of your flock for at least 2 weeks, until you are certain the bird is healthy.

Chickens have a greater chance of remaining healthy if you take the following measures:

• Scrub out waterers and refill them with clean fresh water daily.

• Avoid feeding old or moldy rations.

• Clean out the coop at least once a year. In between, promptly remove wet litter and accumulated piles of droppings.

• Provide enough space at feeders and waterers for even the lowest chickens in the peck order.

• Vaccinate as recommended for your area by your county Extension agent, state poultry specialist, or veterinarian.

• Maintain a stress-free environment, and train your chickens to be calm.

Signs of Illness

Once you become familiar with how a healthy chicken looks and acts, you can easily detect illness by noticing changes. Each time you enter the coop, stand quietly for a few moments until your chickens get used to your presence and go on about their business. Then look for anything unusual.

Sound: The chickens in a healthy flock make pleasant, melodious sounds. Sick chickens may sneeze, gulp, or make whistling or rattling sounds, especially at night.

Smell. Notice how your chicken house usually smells. Any change in odor is a bad sign.

Appearance: A well chicken has a bright, full, waxy comb, shiny feathers, and bright, shiny eyes. A sick chicken’s feathers may look dull, and its comb may shrink or change color. Its eyes may get dull and sunken, or swell shut. Sticky tears may ooze from the corners of its eyes. Its nostrils may drip or become caked.

Droppings. A chicken’s droppings are normally gray with a white cap. The drop pings of a sick chicken may turn white, green, yellow, or bloody or be loose. Occasional foamy droppings, however, are normal.

Behavior. A healthy chicken looks perky and alert, with its head and tail held high. A sick chicken hangs its head or hunches down, sometimes ruffling its feathers to get warm. It may drink more than usual, eat or drink less than usual, or lay fewer eggs. A mature bird may lose weight. A young bird may stop growing.

Dead chickens are, of course, one sign of disease, but don’t jump to hasty conclusions if one chicken dies. The normal mortality rate for chickens is 5 percent per year. Naturally, you’ll be upset when you find a dead chicken, but it’s not a significant issue unless more chickens die or your flock shows other signs of disease.

SALMONELLA

Salmonella is a bacterial disease that can affect poultry. Eggs and meat contaminated by salmonella bacteria pose a significant human health risk. Infected birds may have diarrhea and obvious signs of illness, often leading to death. Carrier birds are those with no signs of illness that pass bacteria to their eggs and to other birds. Be sure to purchase stock from salmonella-free flocks.

Providing Treatment

Properly treating a sick chicken requires knowing what disease it has. Unfortunately, many chicken diseases mimic one another. If you do not know exactly what disease you are dealing with, administering the wrong medication can make things worse. Seek help from an experienced poultry person in your area, your county Extension agent, or your state poultry specialist, or consult a comprehensive chicken health manual.

Definitely call your county agent or state specialist if several chickens suddenly get sick or die at the same time. Your flock may have a contagious disease that could easily spread to nearby flocks. You might take the dead chickens to a poultry pathologist. You won’t get them back, but you will find out what ails them, from which you will learn how to treat the rest of your flock. Your county Extension agent can help you find the nearest poultry pathologist.

If one of your chickens appears sick, immediately isolate it well away from the rest of your flock. To avoid spreading disease, tend your well chickens before feeding and watering the sick one. For the same reason, always tend chicks or growing chickens before taking care of mature ones, even when they all appear to be perfectly healthy.

It’s sad to say, but the best way to treat many diseases is to do away with the sick bird and burn or deeply bury the body. Usually, by the time you notice that a chicken isn’t well, it’s too sick to be cured. By getting rid of it, you may keep its disease from spreading. Even if you do cure the bird, it may remain a carrier and continue to infect other chickens in your flock, and it is almost certain not to frilly recover its reproductive capabilities. Eliminating diseased chickens from your breeding flock helps make future generations more disease resistant.

Feather Loss Chickens lose feathers for various reasons: • The annual molt, during which chickens naturally renew their plumage • Chicks picking newly emerging blood-filled feathers from one another, a form of cannibalism that is prevent able through proper management • Mating, generally among heavier breeds, in which the cock claws off a hen’s back feathers; this feather loss is avoidable by rotating breeding cocks or housing cocks away from hens part of the time • Lice and mites, which cause itching and result in chickens’ pulling out their own feathers |

Lice and Mites

Lice and mites may be brought to your flock by wild birds, rodents, and new chickens. They may be carried on used feeders, waterers, nests, and other equipment; if you recycle used equipment, scrub and disinfect it before putting it to use. Lice and mites bite or chew a chicken’s skin and suck its blood, and a serious infestation can result in death. The habit chickens have of dusting themselves in dry soil, which is infuriating when they get into your garden, helps keep their bodies free of lice and mites.

Periodically check your chickens for lice and mites. Examine them at night, using a flashlight to look between the feathers around the head, under the wings, and around the vent. Also look carefully at the scales along the shanks. You won’t need to check more than a few chickens, since these parasites spread rapidly from one chicken to another.

Lice leave strings of tiny light-colored eggs or clumps that look like miniature grains of rice clinging to feathers. You are unlikely to see the lice themselves, since they move and hide quickly, but you may see scabs they leave on the skin.

Body mites are tiny red or light brown insects that look like spiders crawling on the skin at night. During the day, they inhabit perches and nests. A setting hen on the nest is an easy target for mites.

If lice or body mites get into your flock, dust all chickens with an insecticidal powder. Use only products approved for chickens; these products are available through farm stores and poultry suppliers. Thoroughly clean out your coop and sprinkle insecticidal powder into all the cracks and crevices.

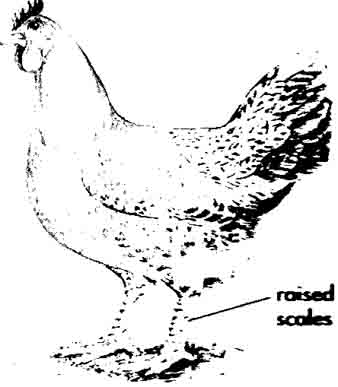

Leg mites get under the scales on a chicken’s shanks, causing them to be raised instead of lying smoothly. A serious infestation is painful and causes the chicken to walk stiff-legged. To control leg mites, once a month coat perches and the legs of all your chickens with vegetable oil. Oral ivermectin is a very effective treatment for infected birds. Consult your veterinarian about the proper formulation and dosage, and be aware that there will be a withholding time after treatment for laying and meat birds.

Raised scales on a chicken’s legs indicate leg mites.

Fecal Analysis: To Find out For sure whether your chickens have worms, scoop some fresh Feces into a plastic bag, seal it, and take it to your vet for analysis. If your chickens have worms, the vet can tell you what kind they are and recommend an appropriate treatment.

Internal Parasites

Different kinds of internal parasites occur in different areas of the United States. The two most common are coccidia and worms.

Coccidia are everywhere, but a properly managed flock develops a natural immunity to them. When coccidia get out of hand, they cause coccidiosis. Although many different animals are affected by coccidiosis, the coccidia that infect chickens do not infect other kinds of animals, and vice versa. Coccidiosis usually affects chicks, but adult chickens can also get it, especially when the weather is hot and humid. The first sign is loose droppings, sometimes tinged with blood. A medication for treating coccidiosis, sold through farm stores and poultry supply catalogs, must be used to treat the whole flock at once.

Worms in chickens are similar to those in dog and cats. A chicken gets round- worms by picking up worm eggs as it pecks for food on the ground. It gets tape- worms by eating an infected intermediary host, such as an earthworm, grasshopper, housefly, ant, snail, or slug. Confined chickens are more likely to have round- worms, whereas foraging chickens are more likely to have tapeworms. Signs of both kinds of worm are droopiness decreased laying, and weight loss, or, in young birds, slow or no weight gain. Loose droppings or diarrhea are also possible. Sometimes you can see worms in the droppings.

To reduce the chances of your chickens’ getting worms, prevent puddles from forming in their yard and keep the coop floor covered with clean, dry litter. Move pastured chickens often. Discourage wild birds and rodents from visiting, and worm any new chicken you bring into your flock.

Parasites in the environment are killed naturally by drying in the sun and, even more effectively, by being frozen in the winter. If your climate is mild, or if you have a particularly mild winter, you may need to perform aggressive parasite control.

Cancer

Only a few forms of cancer occur in chickens, but the ones that do occur with some frequency.

Marek’s disease is caused by a herpes virus. It causes a cancer of lymphocytes, the circulating immune cells. Affected birds are usually less than 4 months old, and they often develop signs of weakness and leg paralysis. Some birds may just sicken and die. Vaccination is an effective preventive measure.

Lymphoid leucosis is also a cancer of lymphocytes, but it occurs in birds older than 4 months and is caused by a different virus. Affected birds often sicken and die. Pale combs, indicative of anemia, may be seen. There is no vaccine for lymphoid leucosis.

Cancers of the ovary and uterus occur in older hens. Any hen more than 2 years old can be affected. Birds with cancer of the reproductive tract may lay misshapen eggs or no eggs at all. They will develop gradual loss of condition, a prominent keel, and an enlarging soft, fluid-filled abdomen.

Next: Summer Care

Prev.: Raising Chicks