No one knows for sure how many breeds of chicken may be found throughout the world. Some breeds that once existed have become extinct, new ones have been developed, and forgotten ones have been rediscovered. Only a fraction of the breeds known throughout the world are found in North America.

The American Standard of Perfection, published by the American Poultry Association, contains descriptions and pictures of the many breeds and varieties officially recognized by that organization. These breeds are organized according to whether they are large chickens or bantam (miniature) chickens, and each group is divided by class.

Large chickens are classified according to their place of origin: American, Asiatic, English, Mediterranean, Continental, and Other (including Oriental). Bantams are classified according to characteristics such as whether they have feathers on their legs. Each class is further broken down into breeds and varieties.

Chickens of the same breed all have the same general type, or conformation. A chicken that looks similar to the ideal for its breed, as depicted in the Standard, is true to type, or typey.

The feathering of some breeds distinguishes them from others. A Polish chicken, for example, has a crest of feathers on its head. The name Polish does not come from this chicken’s place of origin — which is the Netherlands — but from its poll or feathery crown.

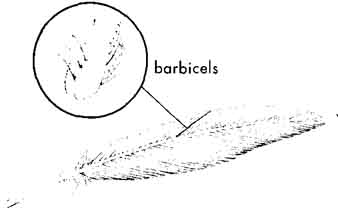

Most feathers have a smooth, satin-like surface called a web. This web is created by barbicels, tiny hooks that hold the web together. If you run your fingers along a feather from top to bottom, the barbicels let go, causing the web to separate. Rub the feather the other way, and the barbicels hook onto each other, bringing the web back together.

A feather with no barbicels looks fuzzy. The feathers of a Silkie have no barbicels, making the bird look like it has fur Silkies differ from other chickens in another way: Most chickens have white or yellow skin, while Silkies have black skin. If you are raising chickens for meat, the skin color may make a difference to you. People of Asian cultures tend to prefer chickens with darker skin, Europeans prefer white skin, and most Americans prefer yellow skin.

Hen feathering also distinguishes one breed from another. A cock usually has pointed feathers on his neck (hackle) and lower back (saddle), whereas hens have rounded feathers in those places. In a hen-feathered breed, however, the cock has round feathers like a hen’s. Sebright bantams are an example of a hen-feathered breed.

FYI: The smooth web of the feather is held together by

barbicels.

Some breeds come in more than one color; each color constitutes a variety. The colors may be plain — such as red, white, or blue — or they may have a pat tern, such as speckled, laced, or barred. Two varieties of the Plymouth Rock are white and barred.

Most chickens are clean-legged, meaning that they have no feathers on their legs. Chickens that have feathers growing all the way down to their toes are called feather-legged. Some breeds, such as the Frizzle, come in a clean-legged variety and a feather-legged variety. (The Frizzle gets its name from its curly, or frizzled, feathers.)

Sometimes a chicken has a tuft of feathers growing under its chin. This trait is aptly called a beard. Some breeds, such as the Polish, come in a bearded variety and a non-bearded variety.

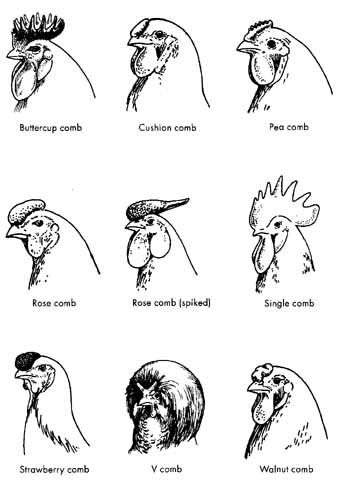

Another feature that may distinguish one variety from another is the style of comb. Most breeds sport the classic single comb, with its series of sawtooth zigzags. The Sicilian Buttercup, by contrast, has two rows of points that meet at the front and back, giving the comb a flowerlike look. Other comb styles are pea, cushion, strawberry, and rose. Rose comb and single comb are two varieties of Leghorn.

With all these different possibilities, how do you choose the breed and variety that is best for you? Narrow your choices by deciding what you want your chickens to do for you:

• Do you primarily want eggs?

• Do you want to raise your own chicken meat?

• Do you want to help preserve an endangered breed?

• Do you want to compete at shows?

• Do you simply want the pleasure of seeing chickens roam your yard as pets?

COMB STYLES: Rose comb (spiked); Single comb; Buttercup comb;

Cushion comb; Pea comb; Rose comb; Strawberry comb; V comb; Walnut comb

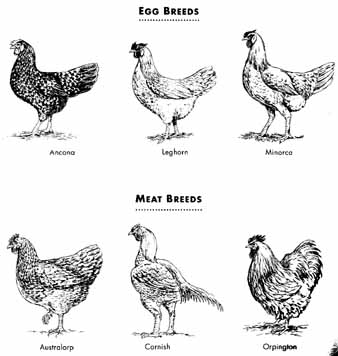

Egg Breeds

All hens lay eggs, but some breeds lay more eggs than others. The best laying hen will yield about 24 dozen eggs per year. The best layers are smallish breeds that pro duce white-shelled eggs. These breeds originated near the Mediterranean Sea, hence their classification as Mediterranean. Examples are Minorca, Ancona, and Leghorn, respectively named after the Spanish island of Minorca and the Italian seaport towns of Ancona and Leghorn ( Livorno).

Leghorn is the breed used commercially to produce white eggs for supermarkets. Leghorns are inherently nervous, flighty birds that are unlikely to calm down unless you spend a lot of time taming them. The most efficient layers are crosses between breeds or strains within a breed. The strains used to create commercial layers are often kept secret, but you can be sure a Leghorn is involved.

Most layers produce white eggs, but some lay brown eggs. Brown-egg layers are calmer than Leghorns and therefore more fun to raise.

After a year or two, the laying ability of hens decreases. Unless you choose to keep your spent hens as pets, the best place for them is the stew pot.

STRAINS A strain consists of related chickens of the same breed and variety that have been selectively bred for emphasis on specific traits, making the strain readily identifiable to the trained eye. Most strains are named after their breeder, although sometimes a breeder will develop more than one strain and give each a code name. Two strains may be so different from each other that generalized comparisons about their breed become difficult. Indeed, sometimes more variation occurs among strains than among breeds. To further complicate matters, the farther a strain gets from its source the more it may change, because the new breeder may not share the vision of the original breeder. “When a strain is taken up by several new breeders, chances are good that each will selectively breed in a different direction until the original strain is barely recognizable. |

Meat Breeds

Good layers are scrawny, because they put all their energy into making eggs instead of meat. If you want chickens mainly to have homegrown meat, raise a meat breed.

The various terms for chicken meat depend on the stage at which the bird is butchered. Broilers and fryers weigh about 3½ pounds and are suitable for frying or barbecuing. Roasters weigh 4 to 6 pounds and are usually roasted in the oven.

For meat purposes, most people prefer to raise white-feathered breeds, because they look cleaner than dark-feathered birds after plucking. The best breeds for meat grow plump fast. The longer a thicken takes to get big enough to butcher, the more it eats. The more it eats, the more it costs to feed. A slow-growing broiler there fore costs more per pound than a fast grower.

Most meat breeds are in the English class, which includes Australorp, Orpington, and Cornish. Of these, the most popular is Cornish, which originated in Cornwall, England. The ideal Cornish hen weighs exactly 1 pound dressed. The fastest-growing broilers result from a cross between Cornish and New Hampshire or White Plymouth Rock. The Rock-Cornish cross is the most popular meat hybrid.

Those 1-pound Cornish hens you see in the supermarket are actually 4-week-old Rock-Cornish crosses, and may not be hens but cockerels (young cocks).

A Rock-Cornish eats just 2 pounds of feed for each pound of weight it gains. By comparison, a hybrid layer eats three times as much to gain the same weight. You can see, then, why it doesn’t make much sense to raise a laying breed for meat or a meat breed for eggs. If you want both eggs and meat, you could keep a flock of layers and raise occasional fryers, or you could raise a dual-purpose breed.

EGG BREEDS: Ancona; Leghorn; Minorca;

MEAT BREEDS: Australorp; Cornish Orpington

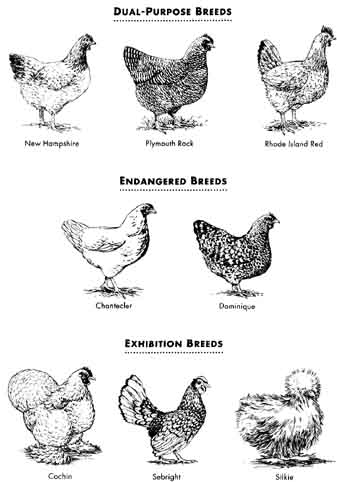

DUAL-PURPOSE BREEDS: Plymouth Rock; New Hampshire; Rhode

Island Red; ENDANGERED BREEDS: Chantecler; Dominique; EXHIBITION BREEDS:

Cochin; Sebright; Silkie

Dual-Purpose Breeds

Dual-purpose breeds kept for both meat and eggs don’t lay quite as well as a laying breed and aren’t quite as fast-growing as a meat breed, but they lay better than a meat breed and grow plumper faster than a laying breed. Most dual-purpose chickens are classified as American, because they originated in the United States. They have familiar names like Rhode Island Red, Plymouth Rock, Delaware, and New Hampshire. All American breeds lay brown-shelled eggs.

Some hybrids make good dual-purpose chickens. One is the Black Sex Link, a cross between a Rhode Island Red rooster and a Barred Plymouth Rock hen. Another is the Red Sex Link, a cross between a Rhode Island cock and a White Leghorn hen. (A sex link is a hybrid whose chicks may be sexed by their color or feather growth.) Red Sex Links lay better than Black Sex Links, but their eggs are smaller and dressed birds weigh nearly 1 pound less.

Each hatchery has its favorite hybrid. Although hybrids are generally more efficient at producing meat and eggs than a pure breed, they will not reproduce them selves. If you want more of the same, you have to buy new chicks from the hatchery.

Endangered Breeds

Many dual-purpose breeds once commonly found in backyards are now endangered. Because these chickens have not been bred for factory-like production, they’ve retained their ability to survive harsh conditions, desire to forage, and resistance to disease.

The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy keeps track of breeds and varieties it believes are in particular danger of becoming extinct and encourages breeders to join its poultry conservation project. Among the breeds on its list is the Dominique, sometimes incorrectly called “Dominecker,” the oldest American breed. A few years ago, it almost disappeared, but it is now coming back thanks to the efforts of conservation breeders. Canada’s oldest breed, the Chantecler, experienced a similar fortunate turn of fate.

While the American Livestock Breeds Conservancy specializes in dual-purpose breeds, the Society for the Preservation of Poultry Antiquities specializes in tracking and conserving endangered exhibition chickens.

Exhibition Breeds

Exhibition chickens are bred for beauty rather than their ability to efficiently pro duce meat or eggs. Some of the same breeds kept for meat and eggs are also popular for exhibition, although the strains are different. Commercial strains used for egg or meat production are often hybrids, but even the pure production breeds are not necessarily true to type. Exhibition strains, on the other hand, are more typy but less efficient at producing eggs or meat.

Even among exhibition breeds, some lay better than others. Exhibition breeds in the Mediterranean class lay better than most other show breeds, even though they don’t lay as well as production flocks of the same breed. Similarly, among exhibition birds, the Cornish and Cochin are more suitable than many others for meat production.

Bantams are miniature exhibition chickens weighing 1 to 2 pounds. They are popular because they eat less and require less space than larger chickens. The shrill crowing of a bantam cock, however, is more likely to irritate neighbors than the lower-pitched crowing of a larger rooster.

Some bantams are small versions of bigger breeds, only one fifth to one fourth the size. Others, such as Sebrights and Silkies, come only in the miniature version. Bantam eggs are smaller than those laid by large chickens; three bantam eggs roughly equal two regular eggs. The American Bantam Association publishes the Bantam Standard describing all recognized bantam breeds, many of which are not listed in The American Standard of Perfection.

Exhibition chickens differ from other livestock in that they don’t come with registration papers. Your only assurances that you get what you pay for are the seller’s word and reputation.Next: Purchasing Chickens

Prev.:

Intro to Raising Chickens