Most ceilings simply cover the bottoms of the joists that support the floor above. If there is no floor above a ceiling, the joists may be smaller than those used for floors—2 x 6s instead of 2 x 8s, for example—and they may be spaced farther apart. Like walls, the surface material of a ceiling is typically drywall, or in older homes plaster over lath.

Drywall and plaster ceilings suffer many of the same ills that afflict walls, but because gravity exerts more pull on horizontal surfaces, ceiling repairs call for different procedures. If a room in your home needs a new ceiling, you can choose traditional materials or light weight pressed-fiber or stamped metal materials that are much easier to work with than either drywall or plaster.

CEILING CONSTRUCTION

Joists do most of the structural work. Not only do they hold the ceiling material (and the floor above, if there is one), they also tie interior and exterior walls together. Inside, 2 x 6-, 8-, or 10-inch joists are usually spaced 16 inches from center to center and toe-nailed to the top plates of bearing walls.

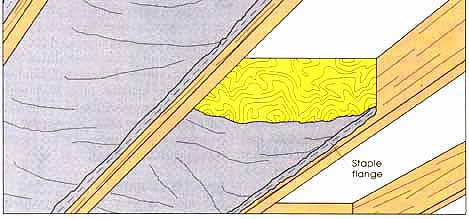

At exterior walls, the joists are also toe-nailed to the wall top plates. If there is an attic above, the joists are face- nailed to the rafters that support the roof and their ends are cut to match the slant (pitch) of the rafters.

If the ceiling is covered with drywall, the panels may be nailed or screwed to the joists or to furring strips that run across the joists. A drywall ceiling is finished with joint compound and tape, just as walls are.

Plaster ceilings start with lath nailed to the joists or to furring strips running across the joists. In old houses lath is closely spaced strips of wood; today expanded-mesh metal lath is used. A base coat of plaster is spread across the lath and forced up into the gaps between the wood lath or through the holes in the metal lath. After the first, rough coat of plaster dries, a second and sometimes a third coat are applied to create a smooth, finished surface.

CEILING CONSTRUCTION includes joists toenailed to the top

plates of interior and exterior walls. Most ceilings are surfaced with drywall

panels screwed to the joists or furring strips, or with lath and plaster.

The circled detail shows the ends of top-floor ceiling joists and roof rafters

resting on the top plate of exterior wall framing. Joist ends are trimmed

to match the slant of the rafters.

REPAIRING PLASTER and DRYWALL

Before patching a plaster or drywall ceiling, ascertain what caused the problem. Cracks and split seams between drywall panels usually result from mi nor settling or the normal shrinking and swelling that wood framing undergoes with changes in humidity. Other than repairing the damage, there’s little you can do about such problems.

Large holes in plaster and sagging ceilings, on the other hand, could mean that water is leaking from a plumbing fixture or the roof. Look for rust spots where nails are located, brownish water stains, or other signs of moisture. If you find them, fix the leak first.

PATCHING CRACKS and SEAMS

If you simply fill cracks or seams with patching plaster or drywall compound, stresses in the ceiling will probably open them up again in a few months. For a durable repair, cover a crack or split seam with self-adhesive fiberglass mesh drywall tape, then apply joint compound. Because it’s more flexible than ordinary paper tape, the fiberglass variety can ride out minor stresses without splitting.

PATCHING HOLES

Fill holes in plaster that are no larger than 4 inches across with patching plaster, as shown earlier. Patch larger holes with drywall. First, locate sound plaster and use a carpenter’s square to draw a square or rectangle around the damaged area. Wearing goggles and a painter’s face mask to protect against plaster dust, chip out plaster within the outline. Next, cut a drywall plug, as explained earlier. The plug will have a gypsum core that fits the opening and a 2-inch-wide facepaper flange around its edges.

Coat the underside of the flange with joint compound, press the plug into the opening, and attach it to the lath with drywall screws. Smooth out the flange and blend its edges into the surrounding ceiling with more joint compound, like taping a wall seam.

LIFTING A SAGGING CEILING

If more than a few square feet of a ceiling are sagging, or if the surface is sagging in three or four different places, it's best to remove those sections and make repairs with drywall patches of the required size. Or take down the entire ceiling and install a new one, as shown below.

Sometimes you can cure minor sagging by lifting the ceiling and driving screws into the joists or lath above. To do this you’ll need drywall screws or flathead wood screws and thin metal plaster washers designed to be countersunk into the plaster. Perforations in the washers help hold patching plaster or joint compound in place.

First, make a T-brace by nailing a short piece of 2 x 4 to a longer one; nail a strip of ½- or ¾-inch plywood to the top of the crossbar to act as a pressure plate. The brace should measure as long as the room is high. Position the brace between the floor and ceiling, then drive wedges under the bottom end to force the ceiling back up against the joists.

Now drill pilot holes into the joists or lath. Slightly countersink these holes with a spade bit the same diameter as the plaster washers. Fit the screws with the washers, drive the screws, and cover the repairs with joint compound.

COVER CRACKS with fiberglass mesh joint tape, then cover

the tape with joint compound. The tape’s flexibility accommodates expansion and contraction. PATCH A SMALL HOLE IN PLASTER by cutting it square and filling

it with a drywall plug as shown. Secure the plug with screws; tape the flange

edges.

FORCE A SAGGING CEILING back in place with a 2 x 4 T-brace,

then fit screws with plaster washers and drive them into the joists or lath.

Countersink the fasteners just enough to cover them with joint compound.

INSTALLING A DRYWALL CEILING

In most respects, putting up a drywall ceiling calls for the same procedures as for walls, so we now focus on the differences between ceiling and wall installations.

First, check building codes—many require id-inch-thick panels for walls but allow lighter, more maneuverable - inch drywall on ceilings. Also, if you’ll be covering the walls as well as the ceiling, install the ceiling first; this way the ends of ceiling panels will rest atop wall panels, which helps support the ceiling and makes taping easier.

PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

You can put drywall over an existing ceiling or attach the panels to exposed joists, but the underlying plane must be even to within 14 inch. Check this by stretching strings diagonally from opposite corners. If the ceiling or joists are uneven, put up furring strips, as shown below.

Next, locate joists (use the stud-finding techniques elsewhere in this guide) and mark their locations on the walls. At this point it’s a good idea to sketch out the framing plan on graph paper and plan cuts in advance. Plot a layout that has panels running lengthwise across the joists, with end joints staggered and meeting at joists. Check corners with a carpenter’s square. If they are square, you can begin dry-walling in a corner; if not, start in the middle of the ceiling and work toward the walls.

LIFTING PANELS INTO PLACE

The toughest part of drywalling a ceiling comes at the beginning when you have to hoist the panels up and hold them in position long enough to drive screws into the joists. If you will be working alone or have a lot of panels to put up, rent a crank-operated ceiling hoist.

If you have a helper or two, improvise a scaffold by laying planks of 2x lumber between two stepladders. Or make a pair of T-braces with crossbars 4 feet wide and center bars as long as the room is high, minus the thickness of the drywall. Use these to wedge the ceiling in place while you drive screws.

PLAN YOUR INSTALLATION on graph paper, noting joist locations.

Full and partial panels should run across joists, with end joints staggered

at joists.

MAKE A SCAFFOLD by laying boards across sawhorses or stepladders.

You’ll need at least one helper to lift the panels into place. Always wear

goggles when doing overhead work.

FASTENING DRYWALL TO THE CEILING

As with walls, you can secure the dry wall with either nails or drywall screws, but screws hold better and it’s not easy to swing a hammer overhead. The screws must be long enough to penetrate 3/4 inch into joists.

Refer to the marks you made on the walls and draw lines across the panels to show where joists are located. Use a screw gun or variable-speed drill/driver to drive pairs of screws spaced 2 inches apart along these lines, with 12 inches from the center of one pair to the next. Work outward from the center of each panel along each joist. If you miss a joist, back the screw out and try again; don't leave the screw in place—it will likely pop out after the ceiling has been taped and painted. Finally, drive single screws 3/8 inch from the ends and edges of each panel. Space the screws 8 inches apart, and locate them opposite one another on each side of seams. If you plan to have floating joints at the walls, don't drive screws at panel edges around the perimeter of the ceiling.

FLOATING WALL-CEILING JOISTS

If you will be putting drywall panels on the walls after covering the ceiling, don’t drive screws at the very edges of the ceiling. Instead, leave those edges free and plan to support them with the wall panels, then tape the joint with fiberglass mesh drywall tape. This system is known as a floating angle. The flexibility of the tape enables the wall-ceiling joint to ride out minor shifting and settling without cracking.

TEXTURING A CEILING

Cover screw dimples with joint compound and tape the joints between panels as you would with a wall installation, but feather the compound out further from the joints—at least 12 inches on each side—because ceiling joints are more noticeable. Use fiberglass mesh joint tape. It’s stronger than paper tape and easier to install overhead.

Even professional drywall tapers find it difficult to achieve absolutely seamless results with ceiling installations, which is why many builders prefer to texture ceilings. Texturing compensates for a less than perfect taping job and can add design interest to a room. Texturing also offers a way to cover up imperfections in an existing ceiling.

Textured paints come premixed or as a powder to which you add water. Applying either type with a long-nap roller creates a stippled texture. For a swirled look, go back over still-wet paint and make circular passes with a whisk-broom or wire brush.

HOW TO PUT UP CEILING DRYWALL:

USE TWO T-BRACES to support the panel. Wedge one into

position and have a helper hold the other, pressing the panel tightly against

the joists while you drive the screws.

stnly_183-1.jpg DRIVE PAIRS OF SCREWS, spaced 2 inches apart, into joists at 12-inch intervals. Space single screws at 8-inch intervals around each panel’s perimeter. don't DRIVE SCREWS at the edges of a ceiling that will be supported by wall panels. A floating angle here minimizes cracking at the joint.

stnly_183-1.jpg TEXTURED PAINT goes on with a long- nap roller. it's much thicker than ordinary paints and helps conceal irregularities in seams between panels. ADD CHARACTER to textured paint by swirling it with a whiskbroom or a stiff-bristle brush. Experiment on scrap drywall to determine the best kinds of strokes.

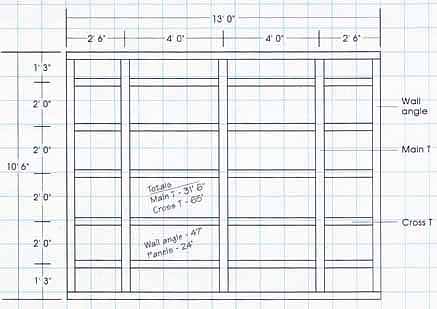

INSTALLING CEILING TILE

Ceiling tiles are a do-it-yourselfer’s dream. Instead of wrestling with sheets of gypsum board, tape, and joint com pound, you can simply glue tiles to a sound existing ceiling or staple them to furring strips. Some manufacturers offer complete ceiling tile systems that include metal furring tracks and special clips to attach tiles to the tracks.

Pressed-fiber or composition-board ceiling tiles typically measure 12 x 12, 12 x 24, or 24 x 24 inches. If you want to reduce noise within a room, use only tiles labeled acoustical; not all tiles have sound-absorbing properties.

If an existing ceiling is uneven or if there is no ceiling at all, you must first put up tracks or 1 x 3 wood furring strips. You may need to box in around obstructions such as heating ducts and large pipes with plywood.

PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

Measure the ceiling and sketch it on graph paper, using each graph square to represent one square foot, the size of a 12 x 12-inch tile. Next, find the mid point of a wall and measure from it to one end wall. If the distance is an even number of feet (tiles) plus 3 inches or more, use the midpoint as the basis for a starting line. If the distance from the last whole tile to the wall is less than 3 inches, move the starting line 6 inches to the left or right. Repeat this process along the room’s other dimension. This ensures that tiles at the edges of the ceiling will be a pleasing width.

Mark the sizes of edge tiles on the graph paper. Count the squares to determine how many tiles you will need and add 5 % for waste. Referring to the sketch, snap chalklines from the midpoints or reference points of opposite walls. Check with a carpenter’s square that they intersect at a 90-degree angle; if not, adjust one line as needed.

Now measure to each side from these starting lines and snap chalklines where the edges of the last full tiles will fall. Make sure these lines are parallel to the starting lines, not the walls, because the room may not be perfectly square.

GLUING TILES TO THE CEILING

An existing plaster or drywall ceiling makes an excellent base for tiles, pro vided it's smooth, with no peeling, blistering, or chalking paint. it's usually easiest to start in a corner and cut a tile to fit. Use a utility knife and straight edge to make the cut. You will use the portion with the tongue edges. Apply daubs of ceiling tile adhesive to the back of this tile; locate the daubs about 1½-inch from each corner and place a fifth daub in the center. Press the starter tile into place with the cut edges against the corner walls and the tongue edges facing outward.

Cut edge tiles to work away from the starter tile along two walls. Interlock each tile’s groove with the tongue of the preceding tile. After you have put up four or five edge tiles along each wall. Fill in with full tiles. Continue with edge and full tiles across the ceiling.

PLAN THE INSTALLATION on graph paper. Measure carefully and check each corner with a carpenter’s square. Compensate for an out-of-square

room by establishing starting lines that intersect at a 90-degree angle in

the center of the ceiling.

GLUE TILES TO AN EXISTING CEILING by starting in a corner and working outward into the room. Mark edge tiles with a pencil and cut

them with a utility knife and metal straightedge. Cut off the grooved sides,

not the tongues.

STAPLING TILES TO FURRING

With exposed joists or an uneven existing ceiling, put up furring strips to staple tiles to. Begin by locating joists and indicating them on your graph paper plan. The furring must be at right angles to the joists and nailed to them.

1. PROVIDE A NAILER at the edges of an open ceiling that run parallel to the joists. Place a 1 x 6 flat against the wall with its bottom face flush with the undersides of the joists. Fasten this nail to 2 x 2 blocking toe-nailed to the joists and the subfloor above. Wear goggles throughout overhead work.

2. CENTER A 1 x 3 FURRING STRIP over the starting line at the center of the ceiling and nail it to the joists. Space subsequent strips 12 inches apart, center to center. Check with a long, straight board; shim low spots with wood shingles to make them level.

3. USE DOUBLE FURRING for in creased clearance below pipes or cable. Nail up a first course of furring 24 inches on center, then nail 1 x 3s at right angles across the first, spaced 12 inches on center, to staple the tiles to.

4. FIT TILES TO A CORNER STARTER. As in gluing tiles to a ceiling, cut a starter tile to fit in a corner and work outward. Glue the starter to the furring. Interlock the grooved edges of each succeeding tile with tongues of those already installed. Secure each tile driving two staples, one on top of the other, through the tongues at each corner. The first staple flares the legs of the second for better holding power.

5. BOX-IN BEAMS and DUCTS with ½-inch plywood, then glue tiles to the plywood. Box-in rectangular ducts, too, r glue tiles directly to them. Cover in side corners with cove molding, outside corners with lightweight metal angle.

6. GLUE OR NAIL THE FINAL ROWS of edge tiles to the furring strips. Finish off the job by installing cove molding around the ceiling perimeter.

INSTALLING TILES ON FURRING:

1. INSTALL A NAILER where joists rest on top of walls.

Cut 1 x 6 lumber to run the length of each wall. Toenail 2x blocking to hold

it in place. 2. NAIL 1 x 3 FURRING across the bottoms of joists. Space the

strips 12 inches on center. Shim by driving a tapered shingle between the

furring and joist.

stnly_185-1.jpg 3. DOUBLE FURRING provides added clearance, if needed. Space the first course at double width. Run the second course of furring strips at right angles to the first. 4. FIT TILE GROOVES onto tongues and drive two staples, one on top of the other, into the corners of the exposed tongues. The second staple flares out for a better grip.

stnly_185-2.jpg 5. BOX-IN DUCTS and beams by nailing plywood to joists as shown. Glue tiles to the plywood and cover joints with cove molding and metal angle. 6. FINISH THE CEILING WITH COVE MOLDING around the edges. If you plan to put up drywall or paneling on the walls, do that before installing the molding.

INSTALLING A SUSPENDED CEILING

Putting up a suspended ceiling is easier than installing furring strips and ceiling tile. You fasten wall angles around the perimeter of the room, hang a grid of main Ts and cross Ts from wires attached to screw eyes in the joists, then tip 2 x 4-foot pressed-fiber panels into place. You can substitute fluorescent light fixtures for some of the panels.

Because they hang a minimum of 4 inches below joists or an existing ceiling, you need to start with at least 7 feet, 10 inches of headroom to achieve the minimum 7½ -foot ceiling height mandated by most codes.

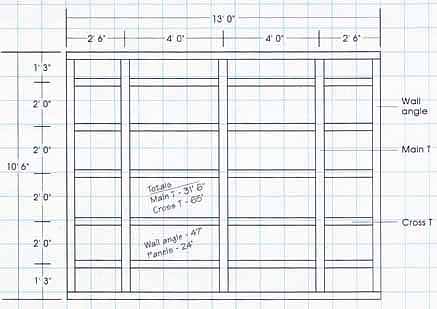

SKETCH A CEILING GRID on graph paper to determine how

many components—wall angles, main Ts, cross Ts, U-channel, and panels—you

will need. A plan also helps you visualize how the panels at the edges will

look and what adjustments to make if necessary.

PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

Much of the effort in installing a suspended ceiling happens on paper, be fore you buy the components. First, measure the room and draw a to-scale plan of the ceiling on graph paper.

To ensure that edge panels will be properly scaled, find the midpoint of a wall that runs perpendicular to the ceiling joists and measure from there to the corner. If this dimension is a multiple of full panels plus 6 inches or more, plan to hang the first main T here; if the coverage is less than 6 inches, shift the T’s location 1 foot to either side of the midpoint. Now do the same on an adjacent wall, one that runs parallel to the joists. If the overage there is less than inches, shift the mid-wall reference point 6 inches one way or the other.

Finally, use the plan to calculate how many feet of wall angles, main Ts, and cross Ts you will need, as well as the total number of panels. Angles and Ts come in standard lengths. Measure the entire perimeter of the room to determine the total footage of wall angle needed. Main Ts will run across one dimension of the room, spaced 2 feet apart; cross Ts will run across the other dimension of the room, 4 feet apart. If you need to hang one section lower than the basic ceiling level in order to box around a duct or other protrusion you will also need lengths of U-channel. The number of panels can be determined from the total area of the ceiling, room length times width. Be sure to count a full panel for each border panel, and be sure to add panels for each side of the box if you plan to drop a section to clear an obstruction.

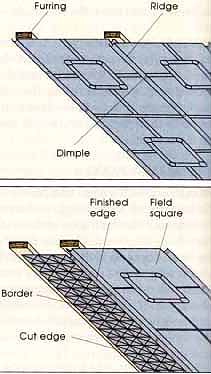

STARTING THE GRID:

INSTALL WALL ANGLES all around the room. These must be

absolutely level, so snap chalk-lines first and check each section with a

level before attaching it in place. SUSPEND MAIN Ts from screw eyes with

wire. Stretch level strings across the room as guides to hang the Is. You

will probably need to cut the last Ito length in each row.

INSTALLING WALL ANGLES

Measure down a minimum of 4 inches from joists or an existing ceiling and snap level chalklines on all walls. Nail or screw wall angles along this line. Angles and Ts typically come in 10- or 12-foot lengths and can be spliced together. Cut them with metal snips or a fine-toothed hacksaw blade.

HANGING MAIN Ts

Snap chalklines across the joists at 2- foot intervals where the main Ts will run. Then stretch strings across the room, parallel with the joists, from wall angle to wall angle. Space them 4 feet apart. They will be a guide for hanging the main Ts at the proper height. Drive screw eyes into every other joist along the chalklines. Refer to your graph paper layout and cut the first main T to length. Set the cut end of this T in position on a wall angle and hang it from the screw eyes with short lengths of wire. Adjust the wire so the bottom of the T just touches the strings. Splice a second T to the first and continue across the room. Cut the last one to fit and rest its cut end on the wall angle.

INSTALLING CROSS Ts

Fit cross Ts, spaced 4 feet apart, between the main Ts. These lock into slots spaced every few inches along the main Is. At the edges you will need to cut the cross Ts to fit; again, rest the cut ends on the wall angles.

INSTALLING PANELS

With some ceiling systems the panels fit into channels in the sides of the Ts; with others the panels simply drop into place from above. Cut edge panels to fit with a utility knife and straightedge.

BOXING DUCTS and GIRDERS

To box around a low-hanging obstruction, install the ceiling on either side, then hang wall angles below the protrusion. Suspend them from the Ts above with wires, and get them level. Next, use a riveting tool to fasten U-channel to the upper Ts. Cut cross Ts and panels to fit horizontally between the wall angles for the box bottom. In stall these, then cut cross Ts and panels to fit vertically between the wall angles and U-channels for the box sides. Measure from the top of the bottom panels. With both bottoms and sides, install one panel, a cross T, then the next panel.

COMPLETING A SUSPENDED CEILING:

SPACE CROSS Ts 4 feet apart along the main Ts. In most

systems the Ts interlock as shown. You will need to cut the cross Ts to length

at the ceiling edges.

ANGLE PANELS up into the space above, then lower and fit

them into the grid. If your ceiling plan calls for lighting fixtures, install

them before the panels.

BOX AROUND OBSTRUCTIONS by suspending wall angles from

the main Ts and riveting U-channel to the Ts above them. Then install panels and cross Ts. Get the bottom panels and cross Ts in place before measuring and installing the vertical side panels and Ts.

INSTALLING A PRESSED CEILING

So-called tin ceilings are actually pressed-metal ceiling systems of light weight sheets of steel stamped with modular designs. Introduced in the 19th century to serve as an inexpensive substitute for plaster or to cover up deteriorated plaster, pressed-metal ceilings have made a comeback and are available in original designs that range from Victorian to Art Deco. A large or ornate design looks best on a high ceiling in a big room. Select simpler de signs with small-figured patterns for low ceilings and smaller rooms.

Pressed-metal ceiling systems usually include three types of components: Field squares (or rectangles) are the major pattern elements; they cover the bulk of the ceiling. Cornices make the transition at the corner, from the ceiling to the wall. Borders bridge between the area covered by the field squares and the cornice. The border has a distinctive pattern that harmonizes with the field square and cornice patterns. It can be cut to width as necessary to adjust the layout so you don’t end up with partial squares at the ceiling edges.

PLAN A FURRING LAYOUT that ha strips around the edges

to which you can nail cornices and border strips. The bottom of the cornice

will be nailed to the wall studs.

ALIGN FIELD SQUARES by fitting the ridged edges together.

At the dimples, drive nails through both thicknesses. Countersink the nails

slightly with a nail set.

CUT BORDER STRIPS to fit between the field squares and the cornice furring. Fit the border’s finished edge over ridges in the field squares and nail through the dimples.

PLANNING THE INSTALLATION

Like ceiling tiles, pressed-metal ceilings attach to 1 x 3 furring strips, but the fur ring grid differs slightly, because you must provide nailers for the cornices and borders as well as the field squares.

As with any ceiling installation, draw a scaled outline of the room. On the plan, space furring for the field squares 12 inches apart, running at right angles to the ceiling joists. Measure the horizontal dimension of the cornice molding—typically 4 - 6 inches; you will need furring spaced this far from the walls around the edges of the ceiling.

Next, subtract twice the cornice’s horizontal dimension from the overall length and width of the room; that will give you the dimensions of the areas to be covered by field squares. Compute how many whole field squares will fit into this space, and make up the difference with borders. Plan to put a row of furring strips at the perimeter of the field square area so that the edges of the field squares will fall on the furring centerline. Finally, determine where the ends or edges of the field squares will overlap. You will need to fit short cross wise strips of furring between the long strips at those points.

Once you have planned the layout, in stall the furring on the ceiling. Use screws or nails long enough to reach in to the joists.

PUTTING UP FIELD SQUARES

Field squares come in strips that mea sure I or 2 feet wide and 2 to 8 feet long. With longer strips, you’ll need a helper. CAUTION: Wear heavy gloves when handling any metal ceiling pieces. The edges are razor-sharp.

Begin at the corner of the room that is farthest from the door, which is usually the most noticeable area of a ceiling. Attach the field squares to the fur ring strips with 3- penny (1¼-inch) nails driven through the dimples that are part of the pattern pressed into the metal. Start nailing at the center of the design and work outward. Use a nail set to countersink the nail heads into the dimples. don't nail the edges or the ends of the panel at this time; the adjoining panels must be put in place first.

Take special care to position this first strip absolutely square to the furring. After that, ridges and dimples along the sides and ends of the strips enable you to align the neighboring components perfectly. Simply position the ridges and dimples in one strip over those in the one you’ve just installed and the squares will fall into line. At the ends and edges, drive nails into the furring through the overlapping dimples. don't yet drive nails into border furring at the edges of the ceiling.

INSTALLING BORDERS

Measure the distance between the centerline of the cornice furring and the edges of the field squares and add % inch for overlapping. Keep in mind that because the room might not be exactly square this dimension may not be uniform from one end of a wall to the other. Cut border material to width with aviation-type metal shears. Plan your cuts so that the border’s finished (ridged) edge will lap the ridge at the edge of the field squares, then nail through the border and field square edges together. don't nail the cut edge of the border at the cornice furring.

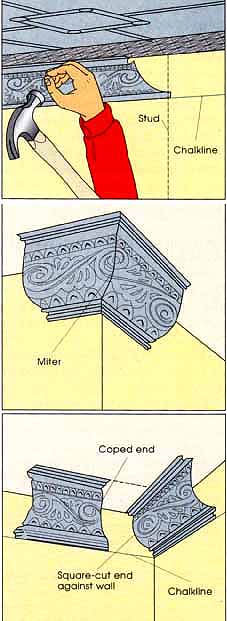

INSTALLING CORNICES

First measure down from the ceiling at several points and snap a level chalkline to mark where the bottom of the cornice will be nailed to the wall. Also locate and mark the positions of the wall studs. Begin installing cornice sections at an inside corner and work toward an outside corner, if any. Some cornices include pre-mitered pieces for inside and outside corners. With others you must miter and cope straight sections as explained below.

1. CUT STRAIGHT SECTIONS of cornice to overlap at the wall studs. Partially drive nails through the bottom edge, into the studs, first. Then nail through the top edge, which overlaps the outer edge of the border, into the ceiling furring. After a section is in position, step back and check to be sure its bottom edge exactly aligns with the chalkline on the wall. Don’t worry about minor deviations on the ceiling; they won’t be nearly as noticeable as irregularities along the wall. After you are satisfied that the wall line is level, countersink the nails with a nail set.

2. AT AN OUTSIDE CORNER try cutting 45-degree angles on scrap cornice material until you get two that make a perfect 90-degree angle. Use these as templates to mark miter cuts.

3. AT AN INSIDE CORNER cope the end of one piece to fit exactly over the contour of another. When your cut-out matches the cornice profile, use it as a template for marking all coped joints. Butt a straight section against one wall, then slide the coped end up against it.

INSTALLING CORNICES:

1. NAIL SECTIONS to the wall studs, then nail through the cornice and border into the furring above. Be sure the cornice’s bottom edge is level

before setting the nails.

2. MITER OUTSIDE CORNERS by making trial 45-degree cuts in scrap material. When you get two that make a right angle, use them as templates for all miter cuts.

3. COPE AN INSIDE CORNER by cutting a straight section to match the cornice pro file. Fit the coped end over a piece with a square-cut end butted into the corner.

SOUNDPROOFING A CEILING

Sound travels in two ways—through the air as airborne noise and through solid materials such as flooring, joists, ceilings, walls, and studs as impact noise. Voices and all but the deep bass notes of a hi-fl system are examples of air borne noise. Typical impact noises include footsteps, vibrations from large appliances in operation, and slamming doors. Some airborne noises, such as musical bass notes, turn into impact noises when they strike a floor or wall and cause it to oscillate.

If sound is moving from one level in your home to another above or below it, first determine whether the problem is airborne noise, impact noise, or a combination of the two. Some paths for air borne noise are obvious, such as an open stairwell, but even tiny cracks or holes in a ceiling can leak surprising amounts of air, and therefore noise. Patching these, as shown earlier, may quiet things down considerably. Because they absorb airborne sounds, acoustic tiles installed on the ceiling and / or walls of a room that is the source of airborne sound can greatly reduce this type of noise.

If, however, a ceiling is transmitting impact noise, installing acoustic tiles in the source room or in the “receiving” room won’t do much to stop it. The sound of footsteps and other blows to the floor above pass right on through. Suspended ceilings perform somewhat better than acoustic tile ceilings, because their hanging wires isolate them from the floor above.

Drywall ceilings can be quietest of all if they include insulation between the ceiling and floor, and if the drywall panels are isolated from the ceiling framing with special resilient Z-channels that function like the double-U wall channels shown earlier. The insulation will absorb sound in the air space between the ceiling joists so that those bays and the ceiling surface don't act together like the soundbox of a guitar. The Z-channels isolate the ceiling surface from impact sound transmitted by the joists themselves.

SOUNDPROOF A NOISY FLOOR with carpet and padding or resilient

flooring installed over underlayment and insulating board. This muffles some,

but not all, impact sounds.

USING RESILIENT CHANNELS:

1. USE Z-CHANNELS to hang drywall from an existing ceiling.

Locate the joists and screw channels into them with 1½-inch drywall screws.

Overlap lengths at joists as shown.

2. FASTEN DRYWALL to the Z-channels, with screws at the edges and midway across each panel. To keep the channels from bending, install screw

A first, then screw B. 3. FIT INSULATION, cut for a snug fit, in to the cavities

between the channels. Tape drywall joints and cover screws with joint compound,

then paint or texture the ceiling.

SOUNDPROOFING AN OPEN CEILING:

1. WITH OPEN JOISTS, first insulate between them with insulation batts or blankets. Staple these to the sides of the joists. The paper or foil barrier surface should face down.

2. SCREW Z-CHANNELS to the joists, leveling the channels with shims if necessary. Attach drywall to the channels as shown above, then finish the joints and paint or texture.

SOUNDPROOFING FROM ABOVE

Before you set out to soundproof a ceiling, determine whether you might be better off quieting the floor above in stead. Blocking sound at its source al ways works better than trying to intercept it later. Carpeting laid over rubber padding absorbs sharp impact noises and deadens the sound of footsteps. To further soundproof a floor, install ½-inch insulating board and underlayment before carpeting the surface.

INSTALLING RESILIENT CHANNELS

If you don’t want to carpet the floor above, or don’t want to lose an inch or so of headroom up there, hang drywall from a finished ceiling or exposed joists with Z-channels. Let’s first look at how to proceed with an existing ceiling.

1. To INSTALL Z-CHANNELS over a finished ceiling, locate the joists and screw the channels to them with 1½-inch drywall screws. Lay out the installation as you would for furring. Space the channels 2 feet apart, measured between the centers of their bottom flanges. The flanges should all point in the same direction. Splice channels by overlapping them at joists and screwing through both thicknesses.

2. ATTACH DRYWALL to the Z-channels. Raise the panels into position and fasten them to the channels with 1-inch-long drywall screws. Drive screws at seams in the order illustrated so as to avoid bending the channels. Leave a 1/8-inch gap along the walls and caulk it later to provide a flexible sound-insulating joint.

3. INSERT INSULATION between the new and old ceiling. As each new drywall panel is fastened to the channel, stuff 2-inch-thick batts of fiber glass insulation into the space between it and the existing ceiling. Before you install the final row of panels, glue insulation to the old ceiling, then put up the panels. Tape drywall joints and fill screw dimples, seal the ceiling’s edges with acoustic caulk, and then paint or texture the ceiling surface.

SOUNDPROOFING AN OPEN CEILING

1. PACK FIBERGLASS INSULATION baits or blankets between the

joists. Staple the flanges of the insulation’s paper facing to the joists to

hold it in place.

2. INSTALL Z-CHANNELS across the joists, leveling them with

shims or furring if necessary. Then attach a dry wall ceiling as described

above. Tape the joints, caulk the edges, and paint or texture the surface.

Some texture compounds also have acoustic properties.

Previous: Home Structure Inspection

Next: Environmental Checklist