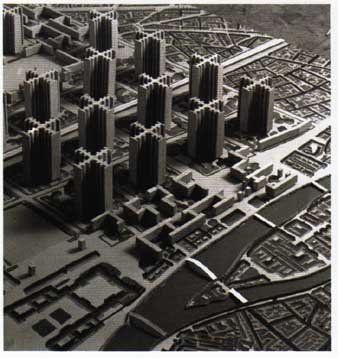

Less than a century ago architects expressed their visions of an urban future based on the new skyscraper typology. Le Corbusier was among the earliest, with his 1923 proposal for the Ville Contemporaine—a series of 60-story glass-clad office buildings set in open parkland above a transportation hub— and his subsequent proposal for the Ville Radieuse (or Radiant City), which extended the concept further by specifying zones for working, living, and leisure. Though never realized in their purest form, Le Corbusier’s radical ideas for reshaping blighted city centers became the foundation for subsequently much maligned high-rise public housing complexes in Western Europe and the United States.

Even more fanciful were some of the ideas of the American architect Hugh Ferriss. In the 192os he imagined skyscrapers that would do more than serve as commercial trophies: they would provide homes to people, be integrated with new forms of transit, incorporate retail and cultural areas, and provide outdoor terraces at great heights. Though he would not live to see it, by the end of the century many of Ferriss’s novel ideas for skyscraper life had become common features of high-rise developments around the world.

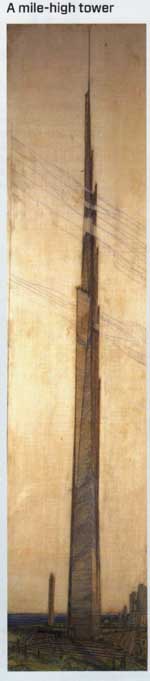

Another celebrated tall-building visionary was Frank Lloyd Wright, who promoted his own revolutionary idea for the skyscraper of the future in 1956. Wright’s proposed Illinois Tower reached a mile into the sky. Its 528 floors and 18.5 million square feet (1.7 million square meters) were intended to serve 100,000 office workers. While the idea was a physical impossibility then, and remains highly impractical today, Wright’s vision became a touchstone of sorts in the ongoing race to the sky.

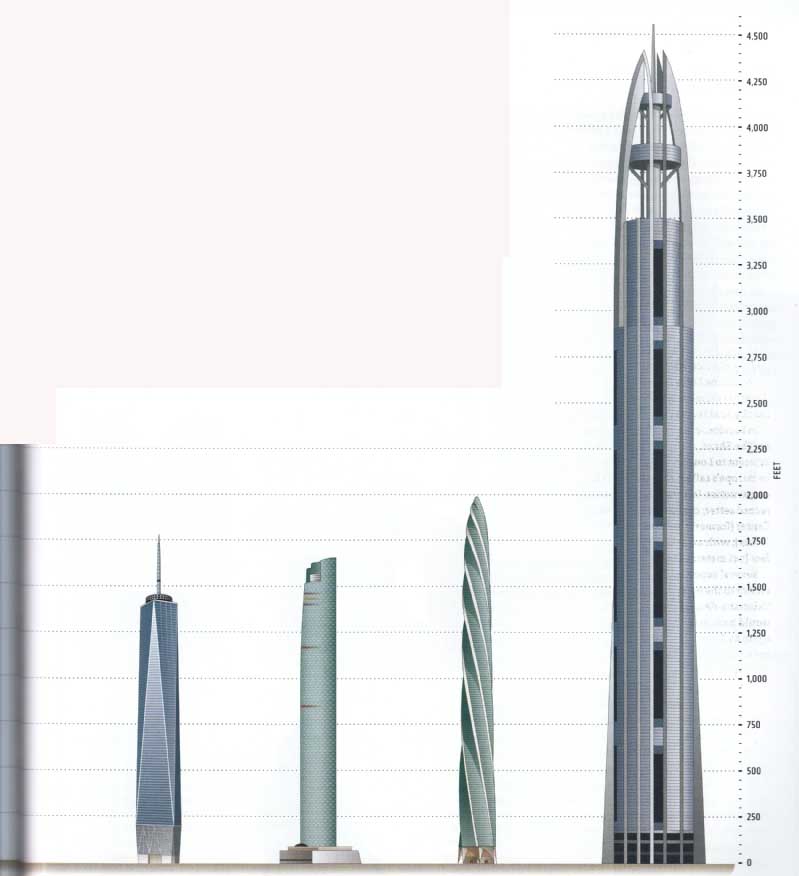

The twenty-first century has brought its own visions of the future—both derivative and unique. The nearly mile-high Nakheel Tower proposed for Dubai replicates in many ways the features of the emirate’s recently opened Burj Khalifa, only taller: it would stretch to 4,600 feet (1,400 meters), nearly 2,000 feet (610 meters) taller than its neighbor. A proposal to build a “ Mile-High Tower” near Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, echoes Wright’s own scheme. The Burj Mubarak al-Kabir in Kuwait is proposed to reach 3,300 feet, or 1,001 meters—a nod to the “Arabian Nights” collection of stories.

None of these projects are likely to move forward quickly (if they move forward at all), given the current financial climate and the time it could take for the global economy to recover. Nonetheless, the proposals are emblematic of certain trends in the evolution of skyscrapers—trends already defining the nature of our twenty- first-century cities.

Most notable, perhaps, is the fact that skyscrapers are no longer an American phenomenon. Like other American inventions that helped define the modern age but were perfected by Asian companies (such as the television, the car, and the radio), the skyscraper is today, in its most aggressive form, largely an Asian phenomenon. Hong Kong has far more buildings over 300 feet (90 meters) in height than New York. The Petronas Towers, in Kuala Lumpur, and Taipei 101, in Taiwan, each held the title of world’s tallest building. And the three new towers in Shanghai’s Pudong district (Jin Mao, the Shanghai World Financial Center, and the future Shanghai Tower) comprise the greatest concentration of supertall buildings anywhere in the world today.

____Architect Hugh Ferriss imagined skyscrapers serving many purposes, including holding up bridges.

Building tall has spread well beyond Asia. Mirroring recent changes in the global economy, the Middle East has also embraced the new urban form wholeheartedly. Hundreds of residential and mixed-use towers have sprung up across the Middle East over the last decade, many incorporating designs and technologies as yet untested in the United States. When the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest building, opened to great fanfare in Dubai in early 2010, it was not alone: 14 other supertall buildings opened in the Middle East between 2000 and 2010 as well.

American influence is still very much apparent in skyscrapers and skyscraper- related technology. Pick any supertall building under construction in Asia or the Middle East and chances are that the architect, structural engineer, or foundation consultant will be American. But the money and the hubris that fuel these multibillion dollar construction projects abroad are distinctly local—and are likely to remain so for the foreseeable future.

==

A mile-high tower:

In the mid-twentieth century, Frank Lloyd Wright publicized his idea for a mile-high tower, the Illinois. Wright imagined it the visual centerpiece of “ Broadacre City,” a community of low-rise homes, each on an acre of land. In many ways his tower had more in common with the church spires of traditional villages than it did with notions of an urban skyscraper.

Wright’s Illinois had 528 floors, with a spire that reached 5,280 feet (1,600 meters) into the sky. To move its 100,000 inhabitants up and down, it relied on five-story elevators running on ratchet interfaces located on the outside of the building (to conserve space in the interior). In total, it covered 18.5 million square feet of space (1.8 million square meters)— almost seven times the size of the Empire State Building.

Though certain aspects of the proposal were intriguing, Wright’s tower could not possibly have been constructed in 1956. All-concrete buildings typically rose no more than 20 stories then. Today advances in concrete technology have resulted in a six-fold increase in concrete’s strength under compression, allowing it to underpin buildings as large as Shanghai’s Jin Mao, at 88 stories.

Though Wright’s tower probably could be built today, it would likely be uninhabitable. Moving people up and down the tower in reasonable time would require elevator speeds well beyond the level of human comfort. Enormous amounts of money and materials would have to be spent reducing sway. And once the lateral load-resisting structure and the number of elevators needed to serve such a large population were in place, there would be little room left for living or working. In other words, the mile-high tower—as august as it sounds—makes no economic or commercial sense.

==

___ Le Corbusier’s urban vision centered on a series of high-rise towers

set in open parkland.

==

How High?

How high the next generation of buildings will go is unclear. Dubai’s Burj Khalifa reaches 2,717 feet (828 meters)—a full 60 percent taller than Taipei 101, the previous holder of the height record. Given its size, the world economic climate, and the lead time involved in constructing a supertall building, the Burj is likely to remain the tallest building on earth for at least the next decade.

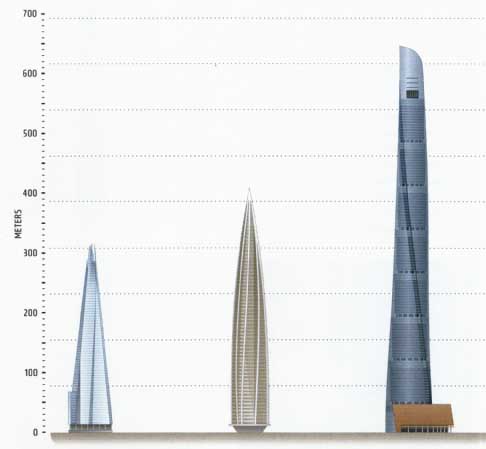

A number of other supertall towers will be completed in the next few years. The 121-story Shanghai Tower, currently under construction, will take its place in 2014 alongside the Jin Mao Building and the Shanghai Financial Center in Shanghai’s Pudong district. Also targeted for completion in 2014 is the Lotte Super Tower in Seoul, Korea. It will reach 1,821 feet (5sii meters) into the sky, making it Asia’s tallest building.

In London, construction has commenced on The Shard, a mixed-use complex adjacent to London Bridge Station that will be Europe’s tallest skyscraper. In New York, construction is under way on another local record setter; completion of 1 World Trade Center (formerly known as the Freedom Tower), with an antenna reaching to 1,776 feet (541 meters), is slated for late 2013.

Several supertall projects have fallen victim to the economic climate. The Calatrava-designed Chicago Spire, which would have made Chicago home once again to America’s tallest building, was put on hold in 2008—after the hole for its foundation was dug. Plans for the 200-story Nakheel Tower in Dubai were suspended indefinitely. Construction of the Gazprom Tower in St. Petersburg was put on hold in mid-2009 and a decision to relocate it made late in 2010.

Like other fanciful buildings, postponed projects like Nakheel may never get built. Supertall buildings are extremely complicated to design, require a very robust leasing and sales market, and take more time to construct than most lenders are willing to accept. Rarely do they incorporate the sort of engineering efficiencies needed to make a development project commercially viable— which means that, absent support from a royal family or a flush private corporation, they simply won’t happen.

==

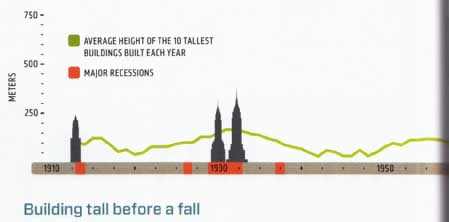

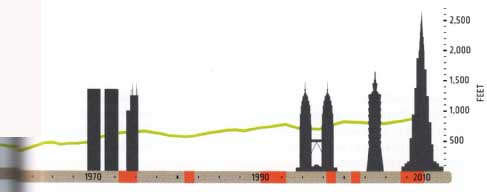

Building tall before a fall:

AVERAGE HEIGHT OF THE 10 TALLEST BUILDINGS BUILT EACH YEAR; MAJOR RECESSIONS

There is a correlation between the timing of record-setting skyscrapers and the economy. The construction of “the world’s tallest building” has historically been initiated toward the end of a boom period, when demand appears strong, debt financing is attractive, and high land prices drive up the number of stories needed to offset land costs. These record setters are rarely finished before a recession has begun and tenants are scarce.

The Shard of London Bridge, designed by Renzo Piano and funded largely by Qatari investors, will become Europe’s tallest tower when it opens in 2012.

The five sides of the Gazprom Tower, originally slated to rise in St. Petersburg, will twist as they reach the sky—if and when it’s built.

The Shanghai Tower will be the world’s first double-skin supertall building, with the world’s highest non-enclosed observation deck, when it opens in 2014.

Such was certainly the case in 1913, with the construction of the Woolworth Building , and again in the late 1920s and early 1970s. The Empire State Building (1931) remained nearly empty for a decade, and the World Trade Center (1973) might have as well had the state government not relocated there. And the Burj Dubai was renamed Burj Khalifa just before its 2010 opening— after the emirate was bailed out by neighboring Abu Dhabi (Khalifa is the United Arab Emirates’ president).

The 123 floors of the Lotte Tower in Seoul will contain retail, offices, residences, a luxury hotel, and an observation deck.

Though ground was broken and foundations laid for Santiago Calatrava’s Chicago Spire in 2007, the project was put on hold in late 2008.

Construction of Dubai’s proposed Nakheel Tower—four separate towers linked at 25 levels by sky bridges—would likely require a decade to complete.

How Green?

Just how sustainable a high-rise tower sheathed in glass can ever be is a subject of ongoing debate among architects and engineers. Certainly the amount of embodied energy and carbon emissions involved in constructing a building at great height will never be offset by environmental credits the building might amass later in life, nor will the energy produced on-site come close to covering the energy demands of the building when tenanted.

Yet new skyscrapers in dense urban areas are, by dint of their location, generally greener than other types of commercial and residential buildings. They are typically located near mass transit, minimizing the fossil fuels consumed by private cars and the negative environmental impacts associated with driving. Vertical living also requires less energy for heat: city dwellers take up less space and use less energy per capita than suburban or rural residents. And these new buildings are designed to last — up to a century or more.

Nevertheless, designers of skyscrapers around the world will continue to go to great lengths to minimize the environmental footprint of new towers. These efforts will take many forms: orienting the building better to the sun and the wind, expanding the use of natural light and ventilation, providing more sophisticated thermal barriers in curtain wall design, maximizing the use of renewable energy (both solar and wind), ensuring better collection and utilization of rainwater, and conserving energy through intelligent building management systems.

In some countries sustainable building practices are now mandated bylaw. As a result of a European Union directive, buildings completed from January 2019 in EU countries will be asked to produce as much energy on-site as they consume—one definition of what is loosely referred to as a “net-zero energy building.” Member states have also been asked to establish two sets of national net energy reduction targets for existing building stock, to be achieved by 2015 and 2020, respectively.

In the United States, the concept of a net- zero or zero-energy building remains elusive. To date there is no agreement on how such a building is defined—whether by its energy cost, its emissions, the energy used on-site, or the total amount of “source energy” (including the energy used to make the energy consumed). And while the absence of a definition has not stopped the federal government from setting long-term net-zero targets for commercial buildings (nor has it stopped states like Massachusetts and California from passing their own energy consumption laws), it remains to be seen how implementable or achievable any of these targets will be in practice.

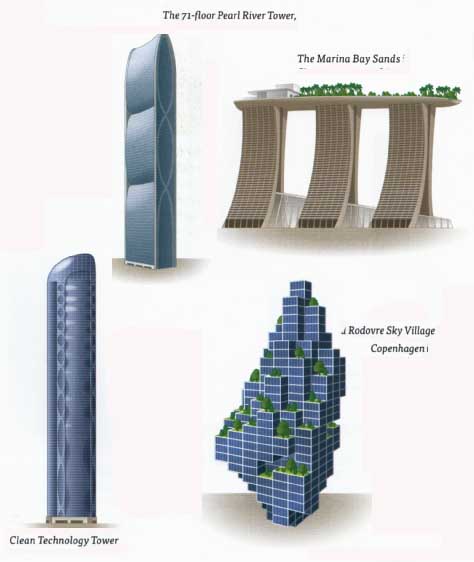

- Harnessing natural forces, Adrion Smith+Gordon Gill’s proposal for the Clean Technology Tower in Chicago places wind turbines at the corners of the building, to capture wind at its highest velocity, and includes a domed double-roof cavity to direct wind toward an array of turbines used for natural ventilation. The dome itself would be shaded by solar cells that capture the southern sun.

- The Marina Bay Sands in Singapore is one of the largest hotel-convention center-casinos in the world, and likely the greenest. Completed in 2010, its three towers support a three-acre (1.2 hectares) “sky park” on the roof, which was lifted into place (5 floors above the city) in sections after the towers were completed. Atone end the park cantilevers out 200 feet (60 meters) beyond the tower’s edge— roughly the length of a 747 airplane.

- The proposed Rodavre Sky Village in Copenhagen is more than a mixed- use building intended to house bath office and residential uses. The tower would consist of stackable green- roofed units, which can serve as office or home (or parking spaces) and whose internal spatial layout offers maximum flexibility to future users of the space.

- The 71-floor Pearl River Tower, a new corporate headquarters for the Chinese National Tobacco Company, is nearing completion in Guangzhou. Its design was driven by the desire to minimize carbon emissions through a variety of features, including photovoltaics, wind turbines, and a high- performance skin.

- The design concept of the ADIC Headquarters, now under construction in Abu Dhabi, derives from traditional Islamic patterns. Conceived as a dynamic façade, the mashrabiya will open and close in response to the desert sun’s path—protecting the most severely exposed parts of the building and contributing too projected 25 percent reduction in the total cooling load.

- The “bioclimatic” design proposed for the EDITT Tower in Singapore features vegetation that spirals from street level upward. Covering half the building, this would form a continuous ecosystem and facilitates ambient cooling of the façade. A rainwater-collection system on the roof and along the façade would direct water through a gravity-fed, water-purification system for reuse.

==

Vertical farming?

Some of the most outlandish proposals for future skyscrapers have revolved around the concept of “vertical farming.” By moving agriculture indoors and relying on hydroponic and aeroponic techniques, one acre (0.4 hectare) of indoor farm can theoretically replace four acres (1.6 hectares) of farmed land outdoors. A 30-story building, it’s estimated, could feed 50,000 people.

To understand farm math, it’s necessary to quantify the waste and environmental damage associated with traditional farming. These “inefficiencies” range from weather-related crop failures to pesticides and agricultural runoff to the emissions resulting from farm equipment like tractors and plows. Vertical farming would, in theory, remove inefficiencies such as these.

The premise relies on a number of rather far- reaching assumptions, including the location of vertical farms at transit hubs along arterials— so that food can be moved to consumer destinations easily. It also assumes sophisticated plant technology, including smart temperature controls that maintain precisely the right growing environment and a “gas chromatograph” that analyzes the “flavinoids” of the plant and indicates precisely the right moment to harvest.

==

What Shape?

Not all tall buildings coming online in the short-term future will be supertall. Most are likely to distinguish themselves in other ways—by the materials used as their skin, by their green credentials, or by their shape.

The shape of today’s skyscrapers is particularly notable. The advances in technology and materials that have allowed buildings to reach 160 stories have also allowed them to take on new and exciting shapes. Today tall towers can twist, lean, and turn back on themselves in ways that would not have been possible 50 years ago. These radical shapes are generally chosen for dramatic effect, but occasionally they contribute to minimizing wind loads by improving a building’s aerodynamic properties.

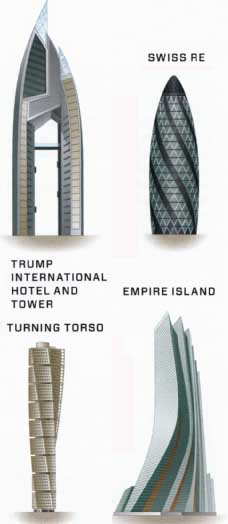

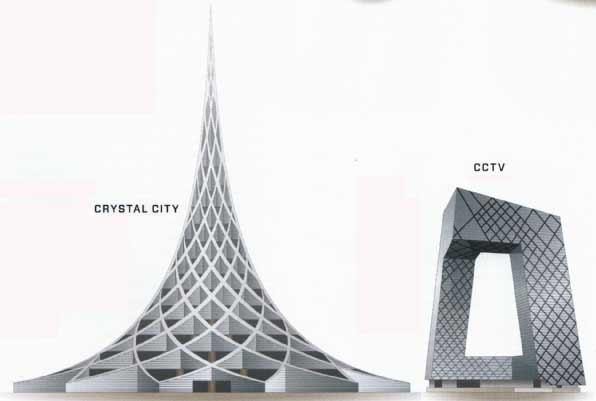

Radical shapes are not limited to any type of building or part of the world. Residential buildings, such as the Puerta de Europa in Madrid or the Turning Torso in Malmo, appear to lean precariously. Office buildings such as the CCTV headquarters in Beijing or the Swiss Re Building in London function proudly as corporate headquarters despite their untraditional shapes. And some complex designs, like the sweeping façade of the proposed Empire Island Tower in the Middle East, have been chosen for mixed-use developments serving hotel, office, and residential users.

TURNING TORSO -- Based on one of his own sculptures and completed in 2005, Santiago Calatrava’s Turning Torso residential building in Sweden is composed of nine units that turn 90 degrees along the tower’s 600-feet (183-meter) height.

SWISS RE -- The unusual shape of Foster+Partners’s London office tower, fondly known as “the Gherkin” since opening in 2004, causes air to move over its surface in ways that assist in ventilating the building.

TRUMP INTERNATIONAL HOTEL AND TOWER -- The proposed design for the Trump Organization’s first venture in the Middle East features a split but connected 62-floor tower, so designed to minimize shadows.

EMPIRE ISLAND -- Located one block from the sea in Abu Dhabi, the proposed Empire Island residential tower sweeps bock on itself to maximize views and light.

CCTV -- Rem Koolhaas’s CCTV Tower in Beijing is the city’s tallest. Its three dimensional “cranked- loop” shape houses radio and television broadcasting studios as well as restaurants and an observation deck.

CRYSTAL CITY -- Conceived as a city within a city, Foster+Partners’s proposed Crystal Island would enclose 27 million square feet (2.5 million square meters) in a tentlike superstructure at a site close to the center of Moscow.

Where?

The shift away from the United States as a home to the world’s tallest buildings has been dramatic and quick. In 1980, 49 of the top 100 of the world’s tallest buildings were located in Chicago and New York— including nine of the top 10. By 2010 this number had dropped to 18. Today, of the world’s top 10 tallest buildings, only the Trump International Hotel and Tower and the Willis (Sears) Tower—both in Chicago—are in the United States.

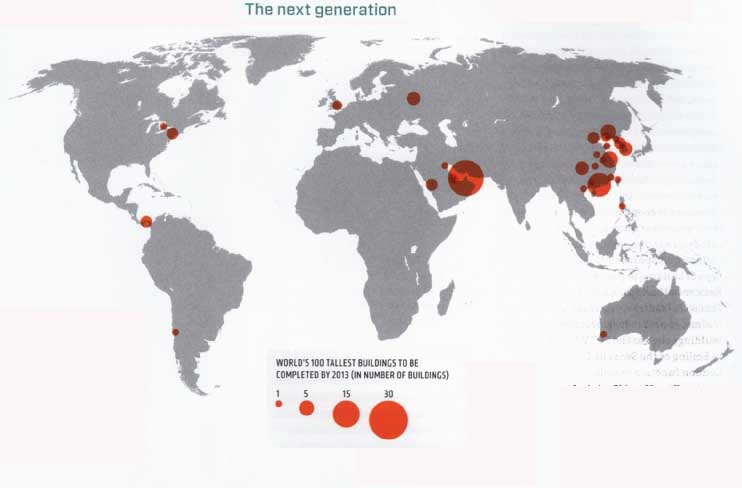

There is no sign that this geographic trend will reverse itself anytime soon. According to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, of the 100 proposed future tallest buildings only five of them would be based in the United States. Nearly two thirds would be located in Asia and more than 20 of them would be in the Middle East. Notwithstanding the fact that many of these will never be built, the number of skyscrapers proposed for the Middle East and Asia indicate an enthusiasm for size that has largely been absent in the United States since the recession following the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001.

Supertalls aside, the construction of “regular” tall skyscrapers has continued over a wider base than ever before. Three quarters of the buildings over 650 feet (200 meters) completed in 2009 were in Asia and the Middle East; only one quarter of them were located in North America. They were spread over 25 cities (nine of them in China)—a far cry from the days when only Chicago and New York embraced the form.

==

The next generation:

- The 100 tallest buildings under construction span the globe, but the number of projects in Asia and the Middle East suggests that the United States will no longer be home to the majority of the world’s tallest buildings.

WORLDS 100 TALLEST BUILDINGS TO BE COMPLETED BY 2013 (IN NUMBER OF BUILDINGS)

- In Asia, China, Hong Kong, and Singapore remain home to active skyscraper construction but have been joined by Korea and India—both of which have record-breaking projects under way.

- This explosion in tall buildings outside of the United States looks set to continue into the next decade. Indeed, more skyscrapers were under construction at the beginning of 2010 (370) than were built in the entire last decade—and in more places. China remains the most active market, but India and Korea now boast a dizzying array of skyscraper construction sites as well.

- In the United States, several supertall skyscrapers have been designed and permitted in Chicago and New York, but the recession has undercut their financial viability, and development work has been halted in many places.

- In the Middle East, tall buildings continue to rise in Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Dubai both for residential and commercial use—though none threaten to rob the Burj Khalifa of its world’s tallest status.

==

How Will We Live?

The skyscraper of the future will bear little relation to the ones of the past. No longer will it serve solely commercial purposes; instead, it’s as likely to be a mixed-use destination—including retail stores, commercial offices, and hotel or residential accommodation. It may also house restaurants and recreational space, supermarkets, movie theaters, swimming pools, or libraries.

The increasing popularity of mixed-use complexes, and in particular the growth in residential towers, has left its mark on every aspect of skyscraper design and construction. In terms of structure, concrete has now overtaken steel as the most prevalent skyscraper material. Representing only 10 percent of the core structural systems of skyscrapers over 650 feet (200 meters) in 1970, concrete today is responsible for a full 40 percent—with another 30 percent of new towers comprised of composite (steel and concrete) beams and columns.

In terms of construction, these mixed-use buildings are far more difficult and costly to erect than single-purpose ones. Often, a concrete residential tower will rise from a steel-framed office podium, increasing the number of trades on the job and making more complex the already delicate job of choreographing construction staging. Add to that the mechanical systems that must support multiple elevator banks, ventilation and plumbing systems, and restaurant facilities, and you have one very complicated construction job.

In terms of design, these mixed-use buildings present the added complexity of segregating users and uses—in terms of pedestrian flows, vertical transportation, noise attenuation, loading, and other services. In designing these buildings, architects must often deal with multiple building code provisions, as standards for commercial and residential occupancy (let alone observation decks and concert halls) often differ.

It’s here, in the design of today’s mixed-use towers, that one finds some hint as to what skyscraper life might be like in the future. Though almost all are privately owned, parts of many mixed-use buildings are today designed to function as a form of public space: witness, For example, the town square-like feel of the retail floors of the mixed-use Time Warner Center in New York at lunchtime almost any day. If historically it was the street or square where the public met to socialize, today it’s increasingly the public portions of mixed-use complexes that act as meeting points for residents, office workers, shoppers, and tourists.

==

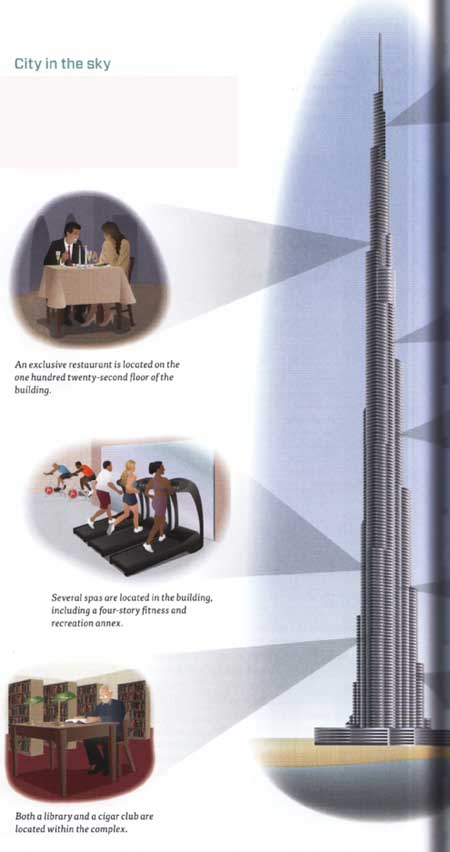

City in the sky

The Burj Khalifa, formerly known as the Burj Dubai, is the first mixed-use building to hold the title of world’s tallest building.

Formally opened in early 2010, it rises to 2,717 feet (828 meters) and contains 160 inhabitable stories. ----

An exclusive restaurant is located on the one hundred twenty-second floor of the building. ---

Several spas are located in the building, including a four-story fitness and recreation annex. ---

Both a library and a cigar club are located within the complex. ---

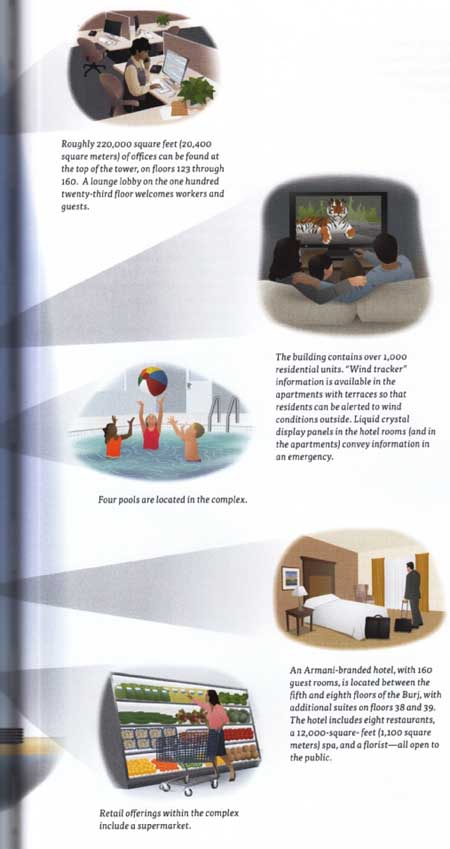

--- The building contains over 1,000 residential units. “Wind tracker” information is available in the apartments with terraces so that residents can be alerted to wind conditions outside. Liquid crystal display panels in the hotel rooms (and in the apartments) convey information in an emergency.

Not all attempts at social mixing depend on transient visitors, and not all happen at or near ground level. Internal sky courts are increasingly appearing on buildings in Asia, driven primarily by the requirement for refuge floors. The new Shanghai Tower, For example, will feature vertical neighborhoods separated by “sky gardens”— intended to combine the best of the indoors and the outdoors in a communal gathering place. Some commentators see these sky courts as a vehicle of social integration, akin to the city’s historic courtyards or the commercial arcades of the nineteenth century—though just how much social mixing will ever occur in private spaces high up in the sky is unclear.

It’s hard to separate the future of the new mixed-use skyscrapers from their impact on the cities around them, and one wonders what someone like Jane Jacobs, one of the great urbanists of the twentieth century, would have had to say about them. In her seminal 1961 work, The Death and Life of American Cities, she railed against the spate of “tower-in-the-park,” tall residential buildings that she felt were, rather than revitalizing blighted portions of American cities, actually robbing them of their diversity.

How well the mixed-use tower of today meets the criteria Jacobs established for a diverse and lively neighborhood is one standard by which we can measure it. Jacobs would have liked the way the combination of residents and businesses operates around the clock but might have bemoaned the fact that users are not always using common facilities. And she would have approved of the density that a mixed-use skyscraper brings. But she would likely have worried about the homogeneity of class and economic status that an all-new building imposes: without subsidies or regulation it’s unlikely to feature low-rent units that bring diversity of both commerce and people.

--- Roughly 220,000 square feet (20,400 square meters) of offices can be found at the top of the tower, on floors 123 through 160. A lounge lobby on the one hundred twenty-third floor welcomes workers and guests.

--- Four pools are located in the complex.

---An Armani-branded hotel, with 160 guest rooms, is located between the fifth and eighth floors of the Burj, with additional suites on floors 38 and 39. The hotel includes eight restaurants, a 12,000-square- feet (1100 square meters) spa, and a florist—all open to the public.

--- Retail offerings within the complex include a supermarket.

The long-term viability of the mixed-use tower as an urban form can also be assessed by measuring its “sustainability.” From an environmental perspective, vertical living makes sense. Energy use in a sprawling suburban home far exceeds that of a city apartment, notwithstanding the fact that today’s glass curtain wall is inferior— in terms of solar and thermal gain—to the traditional masonry façades that preceded it. And city apartment dwellers typically rely on their automobiles far less than residents of suburban or rural areas. Today’s move to “transit-oriented development” means that more and more high-rises are being built at or adjacent to transit—further reducing the amount of roadway traffic and sidewalk congestion normally associated with dense urban cores.

The question of sustainability of form, however, is more than an environmental one: it’s equally an economic and social one. From an economic perspective, the mixed- use typology makes commercial sense. The spaces at lower levels of a mixed-use complex are used for retail and office functions, which require bigger floor plates and easy access from the street or parking; those at the higher levels are reserved for residential and hotel uses, which demand smaller floor plates and can monetize the views. Operating around the clock, they foster an intensity of use and volume of foot traffic that is conducive to successful and stable retail.

Above all, however, it’s the social or sociological sustainability of the mixed-use skyscraper that presents perhaps the hardest questions to answer. Just how well do these “vertical cities” relate to the broader urban fabric? Are these the “urban neighborhoods” of the future or will they become islands onto themselves? Can private sky gardens or elevators ever serve the social mixing purpose that public parks or city streets do? Will mixed-use towers truly lead to more vibrant around-the- clock urban cores or instead to further social stratification? To what extent should municipal planners and governments regulate or incentivize their construction?

It’s too early, of course, in the evolution of this new form of skyscraper to know the answers to these questions. What we do know, thanks to the examples of places like Hong Kong, Singapore, and Manhattan, is that vertical living can be wildly successful and need not rob a city of the diversity that makes it great. We also know, thanks to cities like São Paulo, Mexico City, and Los Angeles, that the alternative means of absorbing large numbers of new city dwellers is horizontal sprawl—which inevitably puts unacceptable demands on both local infrastructure and the environment.

The skyscraper as an urban form, then, is likely to grow in popularity—if only to absorb the great numbers of people moving into our cities. But while it’s too early in its history to assess the ultimate impact of vertical living on the urban environment, it’s never too early for architects and engineers to imagine what skyscrapers could become, just as Frank Lloyd Wright, Le Corbusier, and Hugh Ferriss did almost a century ago.

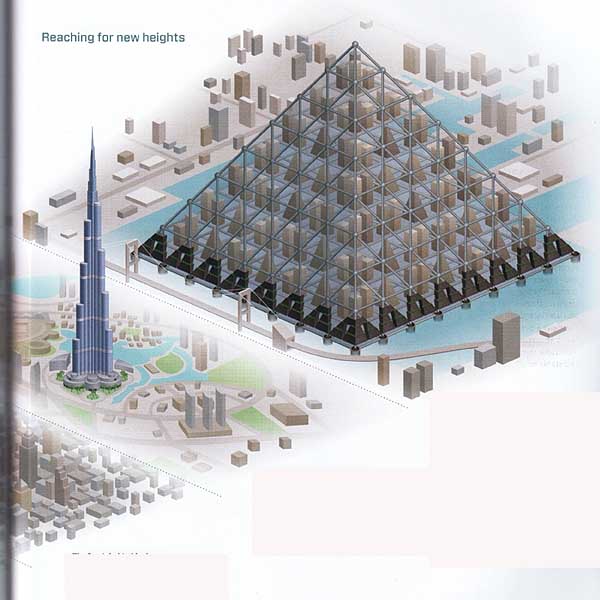

Today their wildest musings are not only about height—though many proposed buildings do seem to defy the laws of both gravity and real estate economics. The skyscraper visions of the early twenty-first century are as much about absolute size, and more specifically about giving form to the idea of “a city within a city.” While the technology to build the most ambitious of these, like the Shimizu Pyramid proposed for Tokyo, does not yet fully exist, the notion of a self-contained city that they celebrate may—like Wright’s mile-high tower—set a direction and a challenge for the skyscraper dreamers of the future.

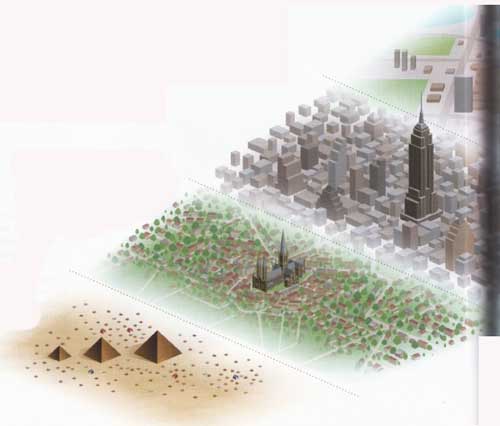

Reaching for new heights

The Great Pyramid of Giza, built in the desert outside Cairo in 2500 BC as a monument to a ruler’s power, was the world’s tallest structure for thousands of years. ---

For centuries the tallest buildings in the world, the great cathedrals of Europe, were located at the center of population hubs and reflected the growth of religious — power during the late Middle Ages ---

--- The first inhabitable skyscrapers were built in the early twentieth century in downtown Chicago and New York—and were solely commercial in nature.

--- The modern idea of mixing people and commerce to create an around-the-clock vertical community came a century later and has been embraced most fully in the Middle East and Asia—sometimes as a way to create density and encourage economic development.

--- Some visions of the future extend the notion of a vertical community by incorporating the idea of a “city within a city.” The proposed Shimizu Pyramid would house 750,000 people in a floating community connected by 86 miles of horizontal and diagonal tunnels and built on 36 massive piers in Tokyo Bay. The design displays a certain historical symmetry by returning to the pyramidal form that marked the beginning of humanity’s race for the sky.

Previous:

Next: