Door locks operate on a simple and ancient principle. A rigid locking arm, called a bolt, is mounted in or on the door so that it can be slid into a socket, or strike, attached to the doorframe. Two types of locks are in wide use today: the key-in-knob (also called a spring-latch lock) and the deadbolt.

Key-in-Knob Locks: The locking arm of this type of lock is activated by a spring mechanism and engages automatically as the door is closed. Most key-in-knob locks are not as secure as a deadbolt, since a burglar can pop the latch out of the strike.

Deadbolt Locks: A deadbolt offers better protection because the bolt must be opened and closed manually by a thumb turn or a key. Generally such a lock is in stalled as a backup to a key-in-knob lock. The simplest kind of deadbolt is a rim lock, which is mounted on the inner face of a door and doorframe; deadbolts that are installed inside a door and lock into a strike box inside the jamb are far stronger.

Some newer key-in-knob designs can be set to function like a deadbolt when extra security is desired. Another versatile locking system is a mortise lock, which combines a deadbolt and a spring-latch mechanism in a single handsome (and expensive) unit.

For any door containing glass, use a double-cylinder deadbolt—that is, one operated by a key on both sides. This will prevent a burglar from reaching through a bro ken pane to open the door.

Special Locks: Other locking systems can serve specialized roles in the home. Sliding doors, for instance, can be locked with a metal bar braced between the frame and the sliding panel, or with a lock that pins movable and stationary panels together. Thumb-activated vertical bolts can help secure a pair of French doors. A strong padlock suffices on most garages, and shed doors need only a hasp and padlock.

Choosing and Installing Locks: When buying any kind of keyed lock, ask for the five-pin cylinder type (be low). Check the wood screws that come with the lock:

Many are too short for secure attachment. Also, keep in mind that even the best lock has little value unless it's installed in a strong door and frame.

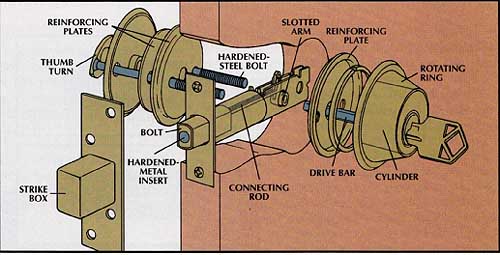

THE INNARDS OF A FIVE-PIN CHAMBER:

The lock most widely used today contains sets of pins and springs in two cylinders—a small one, known as the plug, that fits within another, called the shell. The plug and shell have rows of holes—at least five in the best locks—that line up when the bolt or latch is fully locked (inset, top). In each hole of the shell, a spring pushes against two pins—one in the shell atop a second one in the plug—forcing them down so that the shell pin enters the corresponding hole in the plug, preventing that cylinder from turning.

Inserting a notched key lifts both of the pins in each hole (inset, bottom) so that the separation between every shell and plug pin coincides with the narrow space— called the shear line—between the plug and the shell. Turning the key causes the plug to rotate, since the shell pins no longer engage it. The plug’s action moves the drive bar and activates the latch or bolt.

Such locks have always proved difficult to pick, and refinements to their works have made them even tougher.

One manufacturer, for instance, bevels the pins and the key notches so that the key not only raises the pins but also rotates them; unless each pin is oriented correctly, the plug can't move.

Some locking systems have no key cylinders. In push-button locks the correct combination of numbered buttons must be depressed before the bolt can be moved. and in a computerized system, a magnetically coded plastic card is inserted in a scanner; if the code is correct, the computer activates an electromagnet in the strike box that retracts a bar to disengage the bolt.

A Guardian for the Front Door

A key-in knob lock.

The knob on the outside of this model is keyed, while the inner knob has a thumb turn or button that can immobilize the outer one. Either knob works the lock, since each is linked through a stem to a retractor that connects to the beveled latch and plunger. As the door—locked or unlocked—swings shut, the lip of the strike plate pushes back both pieces. A ridge in the plunger arm raises the retainer bar (inset, top), permitting a notch in the latch arm to slide past and the arm to retract fully. When the door is completely shut, the latch springs out again into the strike box, but the retainer bar pins the plunger in place.

If the inside button is set in the locking position, the latch can't be forced back be cause the retainer bar, no longer supported by the ridge on the retracted plunger, catches in the notch in the latch arm. Turning a key or the inside knob moves an unlocking arm (inset, bottom) that raises the retainer bar and permits the latch to be withdrawn.

The outside knob can't withdraw the locked latch because a pin attached to the locking button engages a notch in the stem of the outside knob, immobilizing that knob. If the inside button is set to the unlocked position, the pin is disengaged from the outside-knob stem; then either the inside or the outside knob can be turned to with draw the latch, allowing the door to open.

A rim lock.

The case of this lock, mounted on the inside of the door, aligns with a strike plate attached to the door-frame. A key from outside and a thumb turn inside operate the lock by turning a drive bar fitted to a catch that raises or lowers a plate encasing the two vertical bolts, which slide into rings in the strike.

A key from the outside and either a key or a thumb turn from the inside rotate a drive bar that fits into a slotted arm in the bolt assembly. The arm pulls or pushes a connecting rod to move the bolt into or out of the strike box. In a good deadbolt lock, the bolt projects 1 inch or more from the door edge and is made of hardened metal or has hardened-metal inserts to resist sawing. Hardened-steel bolts secure the cylinder. Rein forcing plates and rings prevent the cylinder and bolts from being pulled out of the door. A beveled rotating ring, difficult to grip or crush, circles the face of the cylinder. and in models intended for wood doors an internal shield keeps the deadbolt from being forced back with a sharp tool such as an ice pick.

A mortise lock.

This versatile lock combines a spring latch and a deadbolt in a single unit that fits into a large cutout, or mortise, in the edge of the door. The bolt is locked with a key. A button in the faceplate on the edge of the door immobilizes the thumb-piece, which operates the latch. A second button frees the thumb-piece.

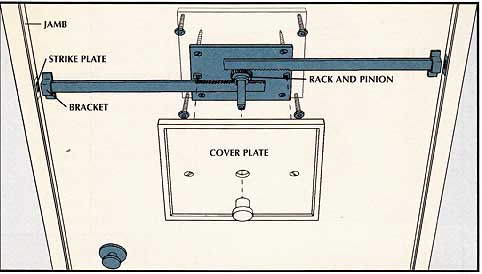

In this high-security lock, de signed mainly for doors that open outward, long steel bars run horizontally along the inside face of the door and slide into strike plates anchored to the vertical studs on each side of the door. The bolts are secured to the door with brackets and are moved by a rack-and-pinion mechanism that is operated by an exterior key-lock and an in side thumb turn set in the center of the door.

A diagonal-bar lock.

This lock, intended for inward-opening doors, has a steel brace whose ends fit in a floor socket and a lock box above the doorknob. The upper end of the brace is secured in the box by a stop and bracket (inset). A key from the outside moves a catch that pushes the bracket sideways (arrows). The bar can then slide upward through a U-shaped retainer ring, permitting the door to be opened far enough for the key holder to reach inside and lift the bar from the floor socket.

Protection for Special Doors

Bolts for a French door.

Recessed in the top and bottom edges of one-half of a pair of French doors— whichever door is opened less frequently—vertical bolts lock into strikes in the threshold (above) and top jamb. The bolts can't be dislodged by force or unlocked by hand through a broken pane of glass. The other door is fitted with a double-cylinder deadbolt lock.

A bar for a sliding door.

A pivoted metal bar drops from the doorframe to a socket on the edge of the sliding panel to lock this door securely in place. A pin across the socket (inset) holds the bar in position and is pulled out to open the lock. When not needed, the bar swings up into a bracket on the doorframe.

Adding a deadbolt.

For extra security, a keyed deadbolt mounted at either the head or the base of the doors (right) locks the movable and stationary panels together, so that the sliding panel can't be pushed open or lifted from its frame. (See above for another way to block lifting of the movable panel.)

Locking Sheds and Garages

Padlocks and hasps.

A good padlock has a hardened- steel shackle, a lock case of solid brass or laminated steel, and a five-pin cylinder, A key turn rotates the cylinder and a rectangular drive bar, retracting the bolts from notches in the shackle (inset). The shackle then pops up, propelled by a spring near the lock base. In locking, a downward thrust on the shackle forces the beveled bolts back until the shackle notches can engage them.

The ring of the hasp, called a staple, should be hardened steel. The hasp edges should be beveled to ward off prying attacks.

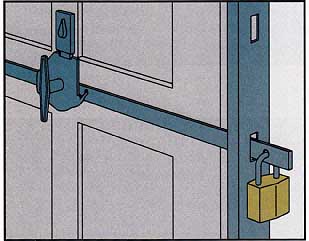

A second lock for a garage door.

A padlock in a hole drilled through the end of a garage door bolt secures the bolt even if the door’s regular lock mechanism is destroyed. Many garage door bolts come with a predrilled hole.

TRICKS-OF-THE-TRADE:

Stopping a Garage Door in Its Tracks: Some garage

doors have bolts that are long enough to pass through the track but too short

to be padlocked as shown above. To double the security of such a door, loop

the shackle of a padlock through one of the holes in the track, positioning

the lock immediately above one of the rollers when the door is shut.

Next: Putting On a Better Lock